ESD Hands-on Course Using Ex Vivo and In Vivo Models in South Korea

Article information

Abstract

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is an established treatment for gastric neoplasias especially in regions with a high volume of gastric cancer. Although ESD has many advantages over endoscopic mucosal resection, ESD is technically more difficult and can result in severe complications. Therefore establishment of an effective training system is required to help endoscopists climb the ESD learning curve. Although a standard training system for ESD remains to be established, some centers are incorporating ex vivo and/or in vivo animal models to provide a safe and effective means of ESD training. However, it is unknown if these animal models are more effective than other programs. Moreover the efficacy of the animal model may vary according to socio-economic status and the volume of gastric cancer. In this article we introduce the basic and advanced ESD training model using the ex vivo and in vivo animal model from South Korea and review the associated literature from other regions.

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is now an established treatment for superficial mucosal lesions of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. ESD not only yields a higher en bloc resection but it also allows complete resection of large tumors that would have previously been impossible to completely resect using the endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) technique. However, ESD is a time consuming and advanced procedure that requires systemic training under supervision of an expert endoscopist. Inexperience in ESD may not only be associated with higher risk for procedural complications (bleeding, perforation), but also with the risk of incomplete resection. Therefore, many centers that perform ESD of the upper and lower GI tract have developed ESD training programs for novice endoscopists. Some of these programs are using ex vivo and in vivo animal models to help novice endoscopists climb the ESD learning curve more rapidly. Although there are many reports of ESD training programs from both the West and East, there is no universal training system. It is likely that training programs will differ according to the culture, incidence of disease and economic situation. However, all programs should commonly focus on safety, effectiveness, reproducibility, and cost-effectiveness. In this article, we will introduce the ESD training program using ex vivo and in vivo porcine model in South Korea.

ESD TRAINING IN SOUTH KOREA

ESD was first introduced in South Korea in 1999. But it was not until 2003 that ESD became a widely accepted practice for the treatment of early cancers. In 2008, ESD was being practiced in 70 tertiary referral hospitals and four community based hospitals (Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service). ESD in South Korea initially focused on early gastric cancers and gastric superficial lesions due to the high incidence of this disease. However ESD was soon also applied to superficial mucosal lesions of the esophagus and colon.

In most centers, beginners of ESD are first required to observe gastric ESD performed by experts. At our center (Digestive Disease Center, Soonchunhyang University Hospital, Seoul, Korea) endoscopists with at least 2 years of GI endoscopic fellowship training and a minimum of 1,000 esophagogastroduodenoscopies and 200 colonoscopies are eligible for ESD training. Trainees are first required to prepare and observe ESD procedures for 3 months (approximately 30 to 40 procedures). During this observation period, the trainee prepares various knives and accessories, learns the steps of ESD, how to approach lesions according to anatomical location and how to control complications such as bleeding or perforation. The trainee also learns how to fix and prepare ESD specimens for optimal pathological analysis.

At our center all trainees are required to examine specimens using stereoscopy and make detailed descriptive reports of the cases they observed. After the observation period, the trainee then participates as the first assistant to one ESD expert for 1 month or 15 to 20 ESD procedures. The trainee is required to manage various knifes, injections, and the electrosurgical unit. During this period, the trainee also coagulates vessels on the post-ESD ulcer base.

After this basic training period, trainees are usually capable of performing ESD starting from relatively small lesions located at the gastric antrum under the supervision of an expert. However, in an effort to facilitate the learning curve, the Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (KSGE) has held annual live ESD demonstrations since 2004 and the ESD study group of the KSGE has organized a nationwide hands-on course using ex vivo porcine models since 2007 and in vivo models since 2009.

ESD TRAINING WITH EX VIVO PORCINE MODEL

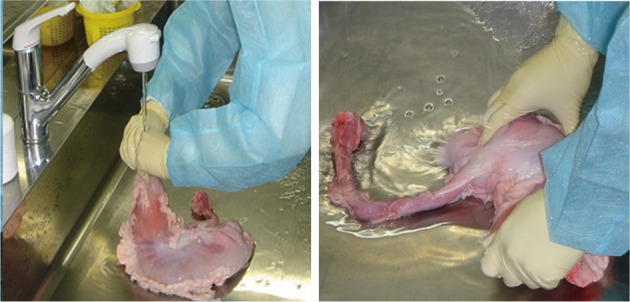

Ex vivo organs are a ready-to-use and inexpensive means to become proficient in basic and advanced ESD techniques as well as natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). Multiple large resections in the esophagus and the stomach may be practiced before the use of a live in vivo model. The ex vivo hands-on course organized by the Korean ESD study group includes a live demonstration of ESD in a porcine stomach model and a hands-on training course using the same model. The ex vivo porcine model was prepared as follows; an irrigated porcine stomach was used for the training course within 24 hours of euthanizing the animal to preserve the elastic properties of the tissue (Fig. 1). The porcine model was kept refrigerated until warming approximately 2 to 3 hours before ESD. The duodenum was closed using forceps and the stomach was immersed in water to detect air leakage. The esophagus was connected to the overtube and fixed within a plastic frame (Fig. 2). Then the stomach was placed within the frame on top of a metal plate and return electrode for electrical current conduction (Fig. 3). Before demonstrating the procedure, a mini lecture of ESD was given to explain the procedure to the attendees. Then trainees performed ESD under the supervision of experts. After completion of ESD, the integrity of the stomach wall can be checked with air insufflations under water immersion.

Preparation of the ex vivo porcine stomach. The stomach is irrigated thouroghly within 24 hours of euthanization.

Preparation of the ex vivo porcine model. The esophagus is connected to an overtube and fixed within a plastic frame.

Configuration of ex vivo model. The duodenum is clamped using forceps and the stomach is placed inside the frame on top of a metal plate and return electrode for electrical current conduction.

The main advantage of the ex vivo model, disregarding the obvious safety issues, is that, since multiple resections can be attempted, a relatively large number of trainees can experience the hands-on course at the same time. Another advantage is the cost effectiveness and relative easiness of preparation compared to the in vivo model. Although there are no studies comparing the ex vivo training model to other training programs, some authors, especially in Western countries with less ESD experience, have reported efficacy and safety of this model as a training program for gastric ESD.1,2 Original ex vivo models have also been developed for esophageal and colon ESD with encouraging results.3,4

ESD TRAINING WITH LIVE IN VIVO PORCINE MODEL

The live in vivo model provides a more realistic environment and provides endoscopists with the opportunity to respond to and to treat potential complications such as bleeding and perforation. The Korean NOTES research group under the KSGE has organized hands-on courses using live porcine models (female swine) for both ESD and NOTES. The live in vivo porcine model was performed under general anesthesia, orotracheal intubation, and mechanical ventilation at an independent veterinary research surgical lab. A veterinary surgeon was present during the course to advise any anatomical issues. All procedures were performed with the animal in the supine position under continuous cardiopulmonary monitoring (Fig. 4). If perforation occurred, an 18 gauge needle was introduced into the porcine abdomen to release the pressure. All animals were euthanized following the procedure with an anesthetic overdose by a veterinarian.

The Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy hands-on course using the live in vivo porcine model.

The main advantage of the live in vivo model is the realistic environment providing similar clinical situations to "human" ESD. Although bleeding is known to be less severe in porcine models, trainees can practice bleeding control as well as endoscopic management of acute perforations. However, live in vivo animal models are more expensive and require certain legal procedures in most developed countries.

ESD ANIMAL MODELS IN OTHER COUNTRIES

Many institutions have reported their experience in animal models for ESD training. In a report from Hong Kong, trainees participated in a 3-day intensive ESD lecture course, a live demonstration of ESD performed for gastric, esophageal, and colonic lesions and a hands-on practical session of ESD using a porcine model under the supervision of expert endoscopists. Twenty-four endoscopists inexperienced at ESD performed gastric and esophageal ESD using a porcine model. During gastric ESD, 15 participants (65.2%) encountered perforations, whereas bleeding occurred during 13 ESDs (56.5%). There were two procedure-related mortalities. The initial performances of ESD were associated with a high incidence of complications, the risk of which not dependent on previous experience in endoscopy.5 In other report of esophageal ESD using live canine models, perforation occurred in the first seven of 10 cases; the last three case were successful.6 Another study using the porcine model for gastric and esophageal ESD reported no serious complications such as perforation or major bleeding in 22 cases (esophagus 7, stomach 15) of ESD performed in six live pigs.2

CONCLUSIONS

Based on our experience and reviews of the available literature, it seems that the use of ex vivo and in vivo models for ESD training is a safe and effective way that may help the endoscopists inexperienced in ESD to climb the learning curve more rapidly. At our institution, however, trainees enrolled in our ESD training program under the supervision of experts were able to perform ESD with similar complication rates to experts. A similar training program in Japan also showed that, under the supervision of experts, novice endoscopists enrolled in a systematic training program were able to perform ESD without decline in clinical outcomes (en bloc plus R0 resection 100% and 96.6%, delayed hemorrhage 6.0%, perforation 2.6%).7 So it seems that in Asian countries, such as Korea and Japan where there is a large volume of early gastric lesions requiring endoscopic treatment, endoscopists can learn ESD, expanding their skill from EMR to ESD, under the supervision of experts. On the other hand, it may be difficult to overcome the learning curve in Western countries where there is a low volume of cases. Therefore, ESD training programs utilizing ex vivo and in vivo animal models may benefit countries with low volume cases the most.

Notes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.