Intramural Hematoma of the Esophagus after Endoscopic Pinch Biopsy

Article information

Abstract

Intramural hematoma of the esophagus (IHE) is an uncommon form of esophageal injury, which may be an intermediate of mucosal tear (Mallory-Weiss syndrome) or transmural rupture (Boerhaave's syndrome). To date, the pathogenesis of IHE has not been well documented. IHE may occur within the submucosal layer of the esophagus following dissection of the mucosa. The most commonly presented symptoms are sudden retrosternal pain, dysphagia and hematemesis. The disorder can occur spontaneously or secondarily to trauma. In this report, we present a case of IHE which occurred after endoscopic biopsy and was recovered following conservative management in a patient who was taking long-term aspirin medication.

INTRODUCTION

Among the acute esophageal injuries, intramural hematoma of the esophagus (IHE) is an uncommon clinical entity. IHE may occur spontaneously1 or secondarily2 to either sudden intraesophageal pressure changes or direct mucosal injury/trauma. Patients usually present with a sudden onset of severe retrosternal pain, dysphagia, or hematemesis. The diagnosis is made by contrast esophagography, esophageal endoscopy, and computed tomography (CT).3 Conservative management is successful in almost all patients, with spontaneous resolution of the hematoma in approximately 2 to 3 weeks.4-6 Despite the increasing number of reports on IHE, many physicians are still unfamiliar with this condition. We report here a case of IHE which occurred after endoscopic pinch biopsy and was recovered following conservative management in a patient who was taking long-term aspirin medication.

CASE REPORT

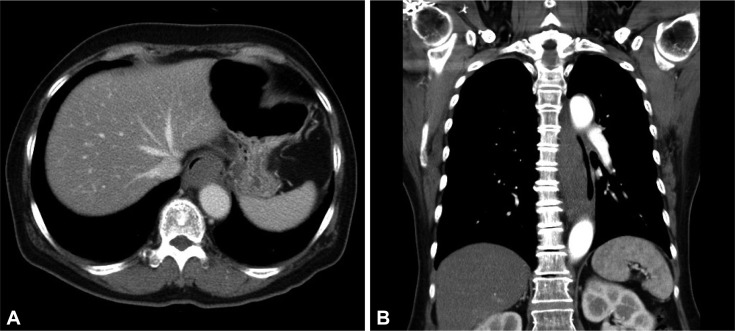

A 60-year-old woman visited our gastroenterology clinic in October 2010 for a routine endoscopic examination. At examination, she was hemodynamically stable. She had a history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus which was controlled with losartan (25 mg), carvedilol (6.25 mg), and glimepiride (2 mg). She also had a medical history of long-term low-dose aspirin intake, and had undergone nephrectomy and total thyroidectomy for incidentally detected renal cell carcinoma and thyroid carcinoma. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy screening was performed. She received an intravenous dose (3 mg) of midazolam for conscious sedation. There was no belching or severe gag reflux during the examination. Black colored spot densities and mucosal irregularities were noted in the upper portions of the esophagus. Small ulcers were observed in the gastric body of the stomach and the duodenum was unremarkable in appearance. A biopsy specimen was taken from the upper esophagus with an Olympus FB-21K-1 biopsy forceps (Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan) (Fig. 1A). Biopsy of the esophagus showed that squamous epithelial cells were normal and not malignant. A bluish swollen lesion was observed through pinch biopsy (Fig. 1B). The hematoma did not expand further after 3 to 4 minutes of observation. After examination, the patient was admitted for observation. Three hours after the biopsy, she experienced worsening chest discomfort, dysphagia, and hematemesis. Physical examination of her chest and abdomen was unremarkable. Routine laboratory studies, including coagulation parameters, were normal. Her chest X-ray and electrocardiogram were unremarkable. She then received emergency esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) which revealed luminal narrowing with an extensive bulge in the posterior wall of the esophagus. A soft bluish submucosal lesion had extended from the upper esophagus to beyond the gastroesophageal junction (Fig. 1C). Chest CT showed an elongated non-enhancing mass involving the posterior wall of the entire esophagus which extended across the gastroesophageal junction into the fundus and body of the stomach (Fig. 2). The patient received conservative treatment with nothing by mouth and total parenteral nutrition. The patient was administered a high-dose acid suppression therapy by continuous intravenous administration of pantoprazole (8 mg/hr). The patient recovered uneventfully and her chest pain gradually subsided. Follow-up EGD performed 12 days later revealed complete resolution of the submucosal hematoma and a longitudinal deep ulcer replacing the previous mucosal tear (Fig. 1D). She was discharged from the hospital in a stable condition. Healing of the esophageal ulcer and complete resolution of the hematoma were confirmed by repeat EGD performed 3 months later.

Endoscopic findings. (A) Black colored spot pigmentation and mucosal denudation was noted at the incision 32 cm of the esophagus. (B) A bluish swollen lesion was observed through pinch biopsy. (C) Soft bluish submucosal lesion was markedly spread along the posterior wall of the esophagus. (D) A 3 to 4 cm linear submucosal ulceration in the absence of active hemorrhage was noted on the lower esophagus.

DISCUSSION

IHE is an uncommon condition within the spectrum of esophageal injuries ranging from mucosal tear (Mallory-Weiss syndrome) to transmural perforation (Boerhaave's syndrome). IHE is also known as intramural esophageal perforation,7 intramural dissection of the esophagus,8 and esophageal apoplexy.9 Cases of IHE have been reported more frequently in middle-aged or elderly females. Elderly patients with intrinsic coagulopathies or who are taking anticoagulant or antiplatelet medication are at higher risk for IHE.10 The three most common presenting symptoms are chest pain, hematemesis, and dysphagia with odynophagia. Other reported symptoms include back pain, epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting.11 Hematemesis may indicate temporary bleeding due to a mucosal tear. Following gradual enlargement of a hematoma, the submucosal layer may become structurally weak and mucosal tear and bleeding may occur at the weakest point.12 Hematemesis frequently occurs at the onset of IHE but stops spontaneously. In the present case, a longitudinal ulcer revealed by follow-up EGD was believed to be caused by healing of the mucosal tear.

The pathogenesis of IHE remains uncertain. Submucosal hemorrhage that dissects the submucosal plane and ruptures through the mucosa is one potential mechanism. The disorder may occur spontaneously,1 or it can be secondary to endoscopic sclerotherapy for esophageal varices,13 esophageal dilatation,14 food impaction,15 improper swallowing of drug pills,16 or coagulopathy.10,17 However, as in our case, endoscopic biopsy is a rarely reported cause of IHE.

Diagnosis of IHE is facilitated by gastrograffin-contrast upper gastrointestinal series (which classically indicates a mucosal "stripe" sign), computed tomography imaging, or esophageal endoscopy.1 CT reveals an elongated non-enhancing mass inseparable from the esophagus containing hyperdense areas. Esophageal endoscopy is also useful but is invasive and may actually precipitate or worsen the condition. Endoscopic findings include a bluish submucosal hematoma which causes bulging of the overlying mucosa.

The general course is uneventful, even when mucosal lesions are extensive. In most patients, complete resolution of their symptoms occurs in 2 to 3 weeks with conservative treatment.4-6 Our patient was also treated conservatively and showed a complete recovery. Most patients can be treated using intravenous nutrition and analgesics with discontinuation of oral feeding. H2 blocker or proton pump inhibitor administration is considered for the suppression of gastric acid production and reflux to the esophagus.18 We therefore decided to administer PPI to prevent additional invasive therapy such as endoscopic therapy or surgery. Surgical intervention usually is required only to control bleeding.19 Sudhamshu et al.20 reported a case of hematoma happened to be incised for biopsy, which resulted in rapid decompression. Cho et al.12 performed an endoscopic incision of the hematoma, in which case the lesion did not resolve spontaneously. All of their patients showed almost complete resolution of IHE. However, Yang et al.18 reported that IHE was exacerbated after endoscopic band ligation. Thus, only rare cases require endoscopic therapy after the failure of conservative treatment, such as in patients with potential airway obstruction, or those with persistent or worsening symptoms.12,20

In many cases, including ours, IHE patients have a medical history of aspirin or anti-coagulant intake. In contrast, Yen et al.,2 Lauzon et al.,11 and Cho et al.12 reported that patients diagnosed with IHE had no prior history of coagulopathy or anticoagulant or aspirin use. However, there were no apparent differences in clinical course between the two occasions (i.e., taking or not taking anticoagulant medication).

Based on our experience with the present case, we believe that even patients with persistent symptoms and mucosal tears from IHE will improve with a conservative approach. In addition, more experience is necessary before a definitive statement can be made. Some cases required endoscopic therapy2 or surgery19 for resolution of IHE. In conclusion, IHE should be considered as a potential complication after endoscopic esophageal biopsy in patients taking long-term aspirin medication. Careful follow-up monitoring is needed for these patients subsequent to endoscopic biopsy.

Notes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.