Endoscopic Gallbladder Drainage for Acute Cholecystitis

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for cholecystitis. However, gallbladder stenting (GBS) has shown promise in debilitated or high-risk patients. Endoscopic transpapillary GBS and endoscopic ultrasound-guided GBS (EUS-GBS) have been proposed as safe and effective modalities for gallbladder drainage.

Methods

Data from patients with cholecystitis were prospectively collected from August 2004 to May 2013 from two United States academic university hospitals and analyzed retrospectively. The following treatment algorithm was adopted. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with sphincterotomy and cystic duct stenting was initially attempted. If deemed feasible by the endoscopist, EUS-GBS was then pursued.

Results

During the study period, 139 patients underwent endoscopic gallbladder drainage. Among these, drainage was performed in 94 and 45 cases for benign and malignant indications, respectively. Successful endoscopic gallbladder drainage was defined as decompression of the gallbladder without incidence of cholecystitis, and was achieved with ERCP and cystic duct stenting in 117 of 128 cases (91%). Successful endoscopic gallbladder drainage was also achieved with EUS-guided gallbladder drainage using transmural stent placement in 11 of 11 cases (100%). Complications occurred in 11 cases (8%).

Conclusions

Endoscopic gallbladder drainage techniques are safe and efficacious methods for gallbladder decompression in non-surgical patients with comorbidities.

INTRODUCTION

Acute cholecystitis is a common medical condition that is conventionally treated surgically. The gold standard of management is cholecystectomy, utilizing either the open or laparoscopic approach.123 It has been estimated that nearly 700,000 cholecystectomies are performed yearly in the United States.4 However, early surgical intervention may result in increased morbidity and mortality in cases involving the elderly, patients with multiple comorbidities, or those with advanced cholecystitis.567 In such patients, urgent or early gallbladder drainage (GBD) can be used either as a temporary measure prior to surgery or as the definitive treatment.891011

Percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD) is an effective measure for the temporary decompression of the gallbladder.10121314151617 However, this procedure is limited in patients with severe coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, or anatomically inaccessible gallbladders.181920 Additional associated risks include catheter dislodgment, cellulitis, pneumothorax, bleeding, fistulas, and infection.710212223 Frequently, the external catheter can cause significant pain and cosmetic disfigurement that can adversely affect the patient's quality of life.24 PTGBD may also need to be performed repeatedly, as the stent may need to be upsized. Moreover, there is a high recurrence rate of cholecystitis when the catheter is removed.61025

Two endoscopic methods, the endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage (ETGD) and endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural GBD (EUS-GBD) have been described in patients who are poor surgical candidates. In retrospective studies, ETGD has a pooled technical success rate of 80.9%.26 This technique may not be feasible if the cystic duct cannot be opacified during a cholangiogram or the guidewire cannot be advanced through the cystic duct into the gallbladder due to tortuosity or obstruction. As an alternative, EUS-GBD has been proposed as a safe and effective method for draining the gallbladder. EUS-GBD involves using EUS to perform a transmural puncture of the gallbladder usually by the transgastric or transduodenal route with the placement of either a drain or stent in the fistula tract in order to facilitate drainage. Recently, this technique, providing drainage through a 5 Fr naso-biliary tube, has been compared with PTGBD in terms of technical feasibility and efficacy. There was no statistical difference between procedures except for significantly lower pain scores in the EUS-GBD group.27 In this study, we evaluated the safety and efficacy of both endoscopic GBD techniques.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data from patients with cholecystitis were prospectively collected from August 2004 to May 2013 from two United States academic university hospitals and analyzed retrospectively. All patients were diagnosed with acute cholecystitis as defined by a combination of clinical symptoms including right upper quadrant pain, fever, positive Murphy's sign, and leukocytosis. Diagnostic radiologic findings included a thickened gallbladder wall, pericholecystic fluid, and a distended gallbladder. All patients were initially managed with bowel rest, intravenous fluids, and antibiotics without improvement. Although surgical consultation was obtained, the patients who were included in the study were not considered operative candidates owing to the presence of comorbidities. ETGD and EUS-GBD were then proposed and informed consent was obtained from all patients. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with sphincterotomy and cystic duct stenting was initially attempted. If the cystic duct stenting was unsuccessful, endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder stenting (EUS-GBS) was then pursued, if deemed feasible by the endoscopist. Percutaneous cholecystostomy was performed in cases where endoscopic drainage was unsuccessful. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Protocol No. 1106011758, approved on 08/2011 by WCMC-IRB).

Materials

All procedures were performed under general anesthesia. Side-viewing endoscopes (TJF-160 or TJF-180; Olympus America, Melville, NY, USA) were used for the ERCP. The 15-cm double pigtail stents of varying diameters (5 to 10 Fr) were used for stenting the cystic duct (Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC, USA). Conventional curvilinear array oblique-viewing therapeutic echoendoscopes were used for EUS-GBD (GF-UCT 180; Olympus America). Fully covered self-expanding metal stents with anti-migratory fins (FCSEMS-AF; Viabil; Conmed, Utica, NY, USA) were placed transluminally. Antibiotics were administered empirically.

Technique

Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage

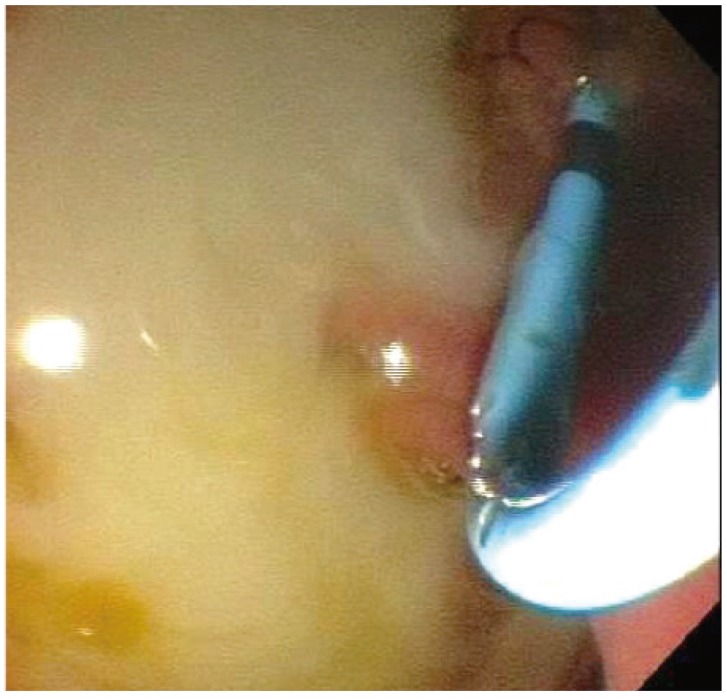

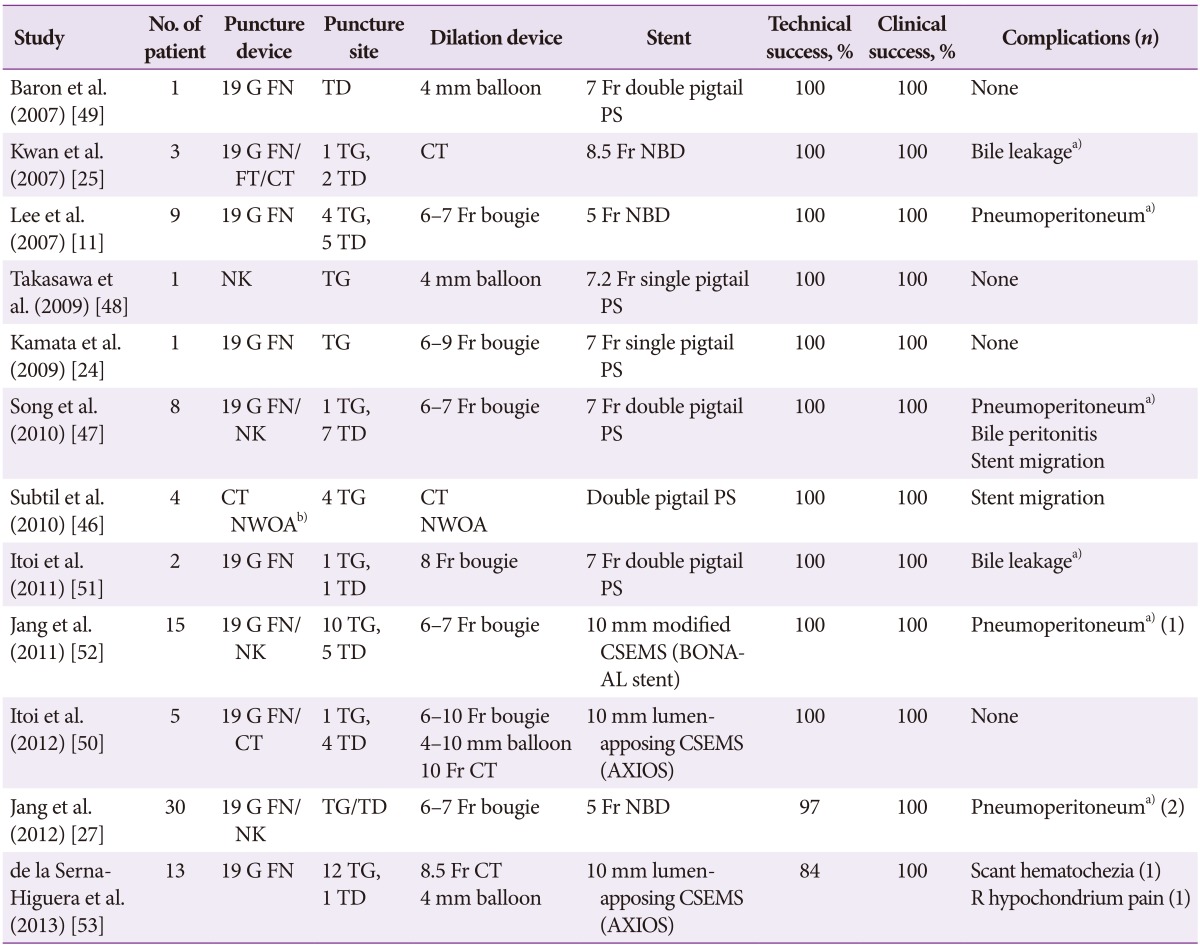

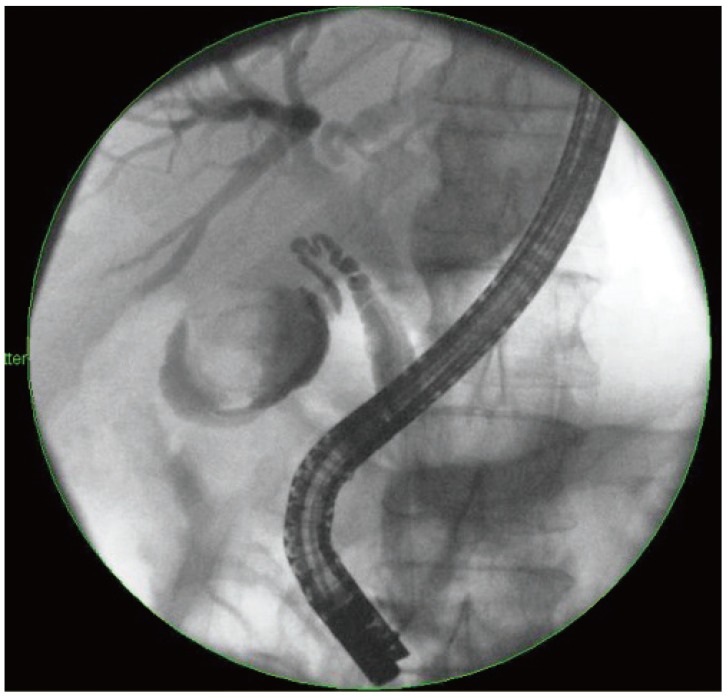

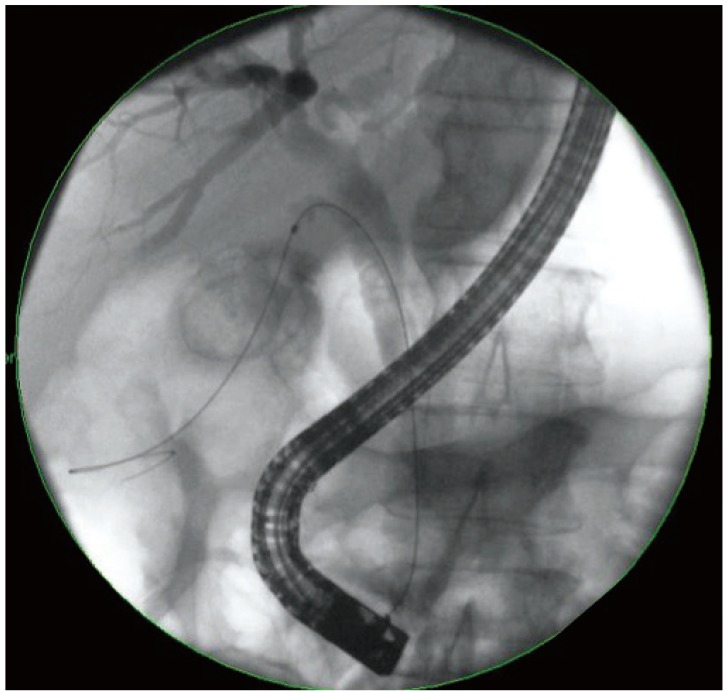

ERCP was performed using conventional techniques. Both a biliary sphincterotomy and balloon occlusion cholangiography were performed in order to define the origin of the cystic duct take off (Fig. 1). A 0.03' Hydra (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) or Terumo (Terumo Medical Corp., Somerset, NJ, USA) guidewire was used in challenging cases in order to advance into the cystic duct using various catheters including a standard sphincterotome, an extraction balloon, or a swing tip catheter (Olympus America) (Fig. 2). Contrast injection confirmed the location. The wire was coiled within the gallbladder. Next, a 4 to 6 Fr dilating catheter (Soehendra Biliary Dilatation Catheter; Cook Endoscopy, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) was advanced over the guidewire in order to fragment cystic duct stones and facilitate anticipated stent placement. Finally, a transcystic double pigtail plastic stent was placed (5, 7, or 10 Fr), crossing the ampulla with a proximal and distal pigtail in the gallbladder and duodenum, respectively, in order to decompress the gallbladder (Figs. 3, 4, 5). Biliary stent placement was performed in cases where delayed biliary drainage was noted on the cholangiogram and revised after 3 months.

Occlusion cholangiogram during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with a balloon catheter showing the tortuous cystic duct and partially filled gallbladder with a large 2.5 cm stone.

Fluoroscopic image of passage of a 0.035-inch hydrophilic Terumo guidewire (Terumo Medical Corp.) from the transpapillary position, through the cystic duct into the gallbladder using a SwingTip endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography cannula (Olympus).

Dilation of the cystic duct tract into the gallbladder using a 6 to 8 Fr Soehendra dilating catheter (Cook Endoscopy).

Deployment of a 7 Fr×15 cm double pigtail plastic stent (Boston Scientific) into the gallbladder from the transpapillary position.

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage

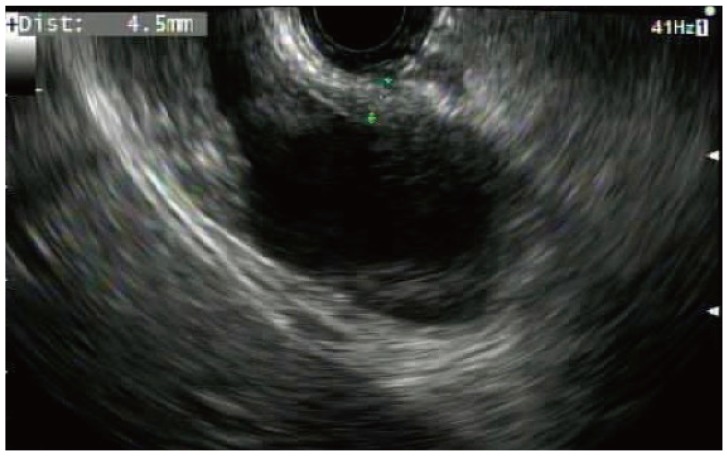

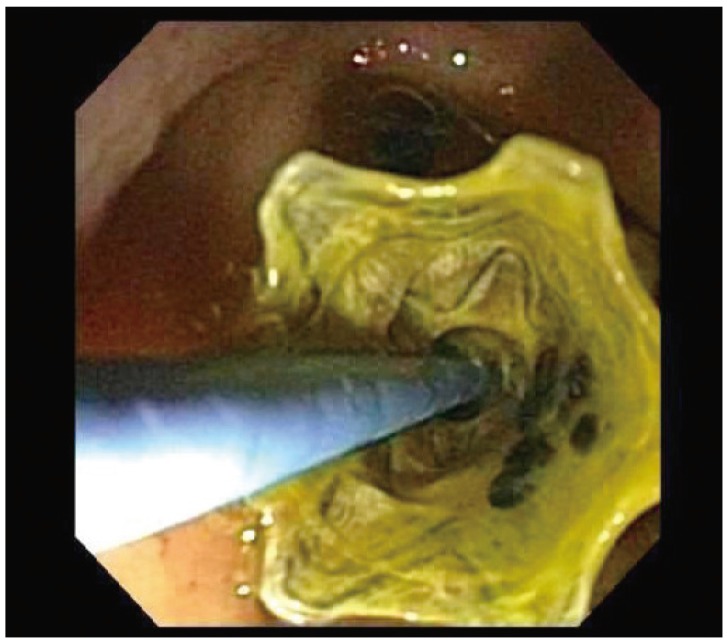

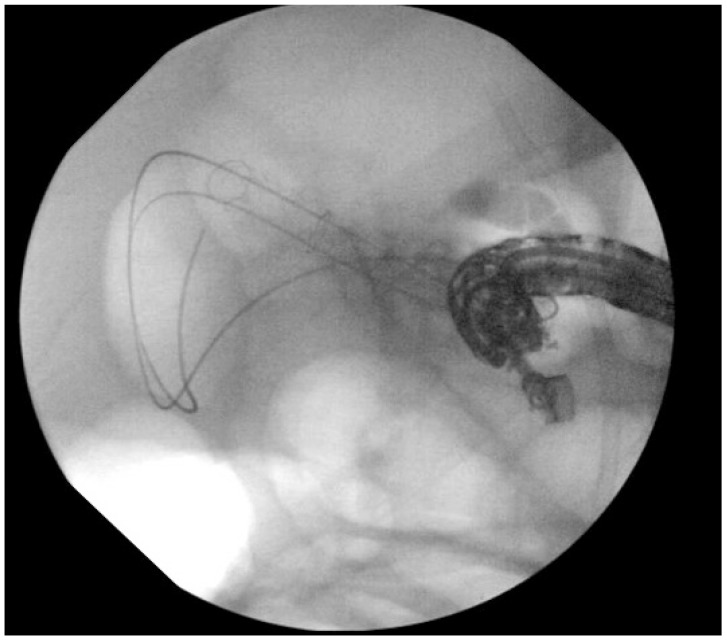

The gallbladder was identified by EUS and examined to ensure adequate proximity to either the duodenal or gastric wall (Fig. 6). Color flow Doppler imaging was used to identify regional vasculature. The puncture site was located either in the duodenal bulb or in the pre-pyloric antrum of the stomach. A 19-gauge needle (EchoTip Ultra Endoscopic Ultrasound Needle; Cook Endoscopy) was used to puncture the luminal wall and advance into the gallbladder under both ultrasound and fluoroscopic guidance (Figs. 7, 8). Bile was aspirated and sent for culture. A 0.035 guidewire was advanced through the needle and coiled into the gallbladder (Fig. 2). A 4 to 6 Fr biliary dilating catheter (Soehendra Biliary Dilatation Catheter; Cook Endoscopy) and/or a 4-mm dilating balloon (Hurricane Balloon; Boston Scientific) were used to dilate the transluminal tract (Fig. 9). A 10 mm×6 cm or 10 mm×8 cm FCSEMS-AF was then deployed across the fistula tract (Fig. 10). A 7 Fr×15 cm or 10 Fr×15 cm double pigtail plastic biliary stent (Cook Medical) was placed through the metal stent to serve as an anchor (Figs. 11, 12).

Endosonographic view of a gallbladder that has been punctured with a 19 G endoscopic ultrasound-guided aspiration needle (Cook Endoscopy).

Fluoroscopic view of a 19 G endoscopic ultrasound-guided aspiration needle (Cook Endoscopy) that was used to puncture the gallbladder from the duodenal bulb using a linear echoendoscope (GF-UC140P-AL5; Olympus).

Passage of a 0.035-inch Hydra Jagwire (Boston Scientific) into the gallbladder though the 19 G needle (Cook Endoscopy) from the transduodenal position.

Deployment of a 10 mm×80 cm fully covered metal stent (GORE VIABIL; Gore Medical) into the gallbladder from the transduodenal position.

Deployment of 7 Fr×15 cm double pigtail plastic biliary stent (Boston Scientific) through the metal stent into the gallbladder.

Definitions

Cholecystitis was confirmed by cross sectional imaging or ultrasonography. Technical success was defined as transpapillary cystic duct stent placement in ETGD and transluminal gallbladder stent placement in EUS-GBD, respectively. Clinical success for both techniques was defined as the complete resolution of clinical symptoms and radiologic evidence of gallbladder decompression.

Patient follow-up

Patients were prospectively followed for stent revision (as deemed necessary by the endoscopist), surgical intervention, or death. Baseline demographics, laboratory data, procedural details, clinical success, and complications were recorded.

RESULTS

From August 2004 to May 2013, 139 patients who were not deemed appropriate surgical candidates due to severe comorbidities underwent endoscopic GBD. Seventy-eight patients (56%) were men with a mean age of 61 years (range, 20 to 90). Drainage was performed in 94 cases (68%) for benign indications, with 15 patients showing cystic duct stones on initial imaging: choledocholithiasis (n=34), cholecystitis (n=16), benign biliary stricture (n=15), cholangitis (n=7), chronic pancreatitis (n=7), acute pancreatitis (n=3), ampullary adenoma (n=3), bile leak (n=2), cholelithiasis (n=2), obstructive jaundice (n=2), alcoholic hepatitis (n=1), biliary colic (n=1), and cirrhosis (n=1). Drainage was performed in 45 cases (32%) for unresectable malignant indications including pancreatic cancer (n=23), cholangiocarcinoma (n=9), external compression (n=5), hepatocellular carcinoma (n=2), lymphoma (n=2), as well as ampullary (n=2), duodenal (n=1), and gastric cancer (n=1) (Table 1).

Clinical and technical success

Endoscopic GBD was attempted by ETGD and EUS-GBD in 128 and 11 patients, respectively. Success was achieved with ERCP and cystic duct stenting in 117/128 of cases (91%). In patients where EUS-GBD with transmural stent placement was pursued, 11/11 (100%) had successful gallbladder decompression. The overall success rate was 92%. Technical success translated to clinical success. All failures were managed with percutaneous drainage.

Success in malignant cases

The success rate in malignant cases was 93% as compared to 91% in benign cases. There were 11 failures using the transcystic approach, three of which occurred in malignant cases while the remaining eight occurred in benign cases.

Adverse events

Adverse events that occurred in 11 cases (8%) included post-procedural pain (n=3), post-ERCP stent migration (n=2), fever (n=2), pancreatitis (n=1), sphincterotomy bleed (n=1), perforation of the gallbladder/bile duct requiring PTC (n=1), and sepsis (n=1). Nine of the complications occurred in patients with benign indications, while only two occurred in patients with malignancies. The mean follow up time was 32 months (range, 1 to 87).

Long-term follow-up

One patient developed spontaneous migration of a transcystic double pigtail stent and underwent single port laparoscopic cholecystectomy while another patient previously deemed too unstable for surgery, showed improved heart condition after EUS-GBD and underwent open cholecystectomy 3 months later. During the follow-up period, a total of 45 patients died, 36 with malignancies and progression of disease, while nine patients with benign diseases died owing to their co-morbidities.

DISCUSSION

Cholecystitis occurs in response to the impaired passage of bile through the cystic duct. More than 90% of cases are caused by obstruction of the cystic duct or neck of the gallbladder by gallstones.28 Other causes, such as tumor involvement at the origin of the or occlusion of the cystic duct by metal stents placed for malignant common bile duct obstruction, respectively, have been described.29 Cholecystectomy is the mainstay of treatment for acute cholecystitis. However, it is associated with increased postoperative morbidity and mortality in patients with cirrhosis, cardiopulmonary disease, malignancy, or other significant medical illnesses.30 In such cases, PTGBD, ETGD, or EUS-GBD have been successfully used as alternative therapeutic procedures.

Although PTGBD can be considered as a bridge to elective surgery, it has several complications including bleeding, pneumothorax, pneumoperitoneum, bile leakage, and accidental catheter dislodgement.10 In addition, the duration of percutaneous drainage has not been standardized.

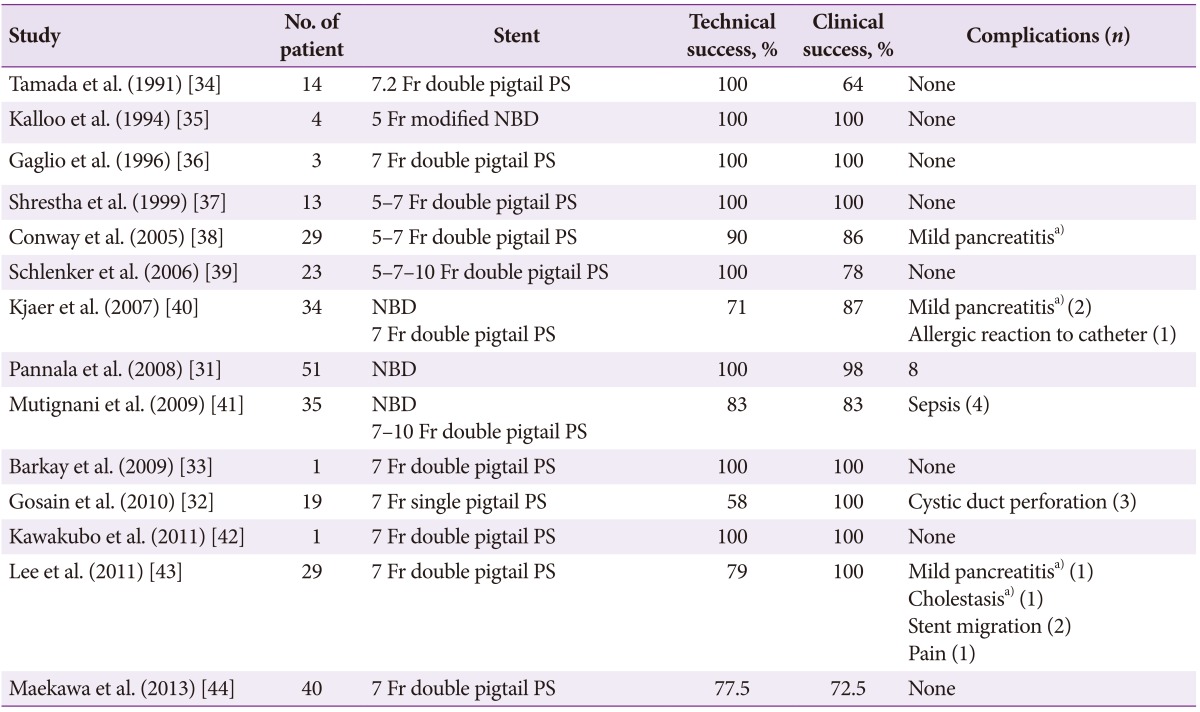

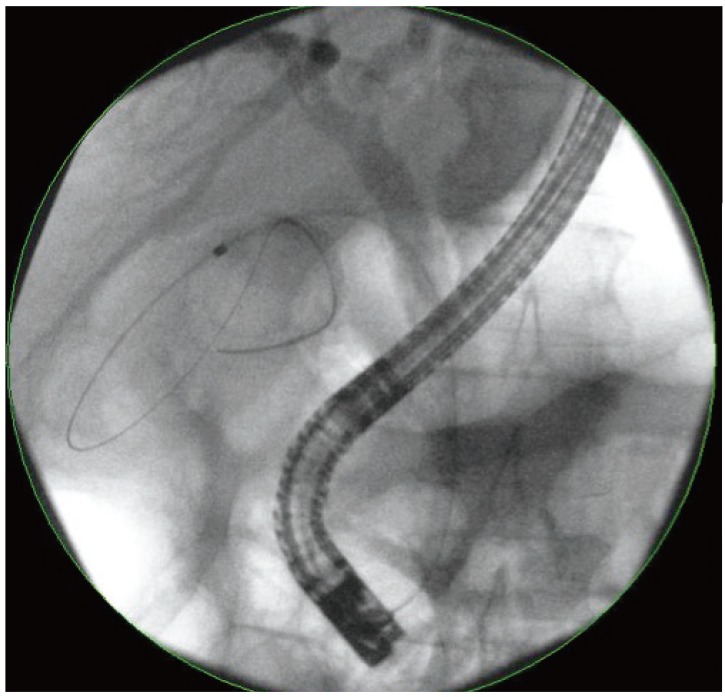

As an alternative, endoscopic methods of GBD are increasingly being employed in expert centers (Table 2).3132333435363738394041424344 Pannala and colleagues31 reported the largest case series in the published literature, to date, with 51 patients who underwent endoscopic GBD for acute cholecystitis. The technical and clinical success rates of 100% and 98%, respectively, support this procedure's potential utility for both the treatment and prevention of cholecystitis in patients who are poor surgical candidates.45

Internal drainage is often preferable due to increased patient comfort and decreased likelihood of the drain being dislodged. Multiple stents have been described in the literature, typically involving the 5 to 7 Fr double pigtails plastic stents (Tables 2, 3).112425274647484950515253 The stent may act as a "wick," with bile flowing around the stent, so stent patency itself is not imperative to maintaining bile flow from the gallbladder.54

There are some risks and limitations associated with GBS. Although cystic duct perforation is a primary concern, the majority of cases can be managed conservatively and the risk is balanced by the long-term benefit of gallbladder decompression.32

Another limitation of ETGD is that it can be technically difficult to perform in some patients and requires a skilled endoscopist to negotiate the cystic duct in patients with acute cholecystitis.46 This is often challenging, due to inflammatory strictures, tumor involvement, stones, a previously placed metal stent, or tortuosity of the duct.47 Occasionally, the cystic duct diverts from the common bile duct and cannot be identified on the cholangiogram. Two reports have previously described the use of the Spyglass cholangioscope for direct visualization of the cystic duct with subsequent advancement into the gallbladder and stent placement.3355 When ETGD is not feasible, EUS-GBD can be pursued, since it is not limited by the configuration of the cystic duct and offers the advantage of eliminating post-ERCP pancreatitis.11

EUS-guided transluminal drainage techniques have gained acceptance as an effective method in treating multiple conditions including pseudocyst drainage,56 abscess drainage,57 and pancreaticobiliary drainage, respectively.5859 Given the high success rates of these techniques, EUS-GBD may be a useful alternative for patients who are not surgical candidates.47 Several case series involving the utilization of the EUS-GBD procedure are described in the literature (Table 3). Punctures directed toward the neck of the gallbladder are typically preferable because the neck is fixed at the gallbladder bed in the liver and connected to the extrahepatic bile duct by the cystic duct.48 In addition, the inflamed gallbladder may have adhered to adjacent structures preventing leakage after the puncture.49 Lee and colleagues11 have proposed that using the transgastric approach into the body of the gallbladder might be better in patients undergoing delayed cholecystectomy because adhesions around the puncture tract could be easily peeled off when the body of the gallbladder is punctured from the antrum of the stomach; however, this technique might have a higher possibility of bile leakage and stent migration as decompression occurs.1150 We prefer the transduodenal approach because the duodenum is anatomically closer to the gallbladder, which yields a shorter fistula tract.51 We do pursue the transgastric approach when blood vessels are interposed between the duodenum and the gallbladder or the technical maneuver with the scope is not feasible. The fistula tract can be created using cystoenterostomes, dilating catheters, or balloons. Some preference has been shown for cystoenterostomes because the tissue desiccation created by an electrosurgical device may result in long-term patency of the fistula as compared to only physical disruption caused by dilation.25 Occasionally there can be difficulty advancing a dilating catheter or balloon over the guidewire and across the GI tract and gallbladder walls.51 Cautious use of a needle knife can be useful in this situation.

EUS-GBD has been recently compared to PTGBD without observed differences in safety and feasibility, but with significantly less post-procedural pain.27 EUS-GBD may be favorable as compared to PTGBD because it avoids complications such as hematoma and pneumothorax. In addition, the transmural approach can be considered in patients with perihepatic ascites.11

Our results support the constantly evolving literature on the high technical and clinical success rates and concurrently low complication rates of endoscopic drainage of the gallbladder in patients who are poor surgical candidates. We propose a therapeutic algorithm for acute cholecystitis in patients with a high risk of surgery due to comorbidities or poor prognosis due to malignancy with an initial attempt at a transpapillary GBD approach via ERCP (Fig. 13). If this approach is not possible, we then recommend the EUS-GBD. Finally, if endoscopic drainage is not successful, PTGBD can be performed. Both the ETGD and EUS-GBD are performed prior to considering percutaneous decompression in order to provide internal drainage, which is less invasive and physiologic. Additionally, internal drainage improves patient pain and quality of life, which is an important consideration. These modalities are technically feasible, safe, and effective techniques in patients at high risk for cholecystectomy.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest: Michel Kahaleh has received grant support from Boston Scientific, Fujinon, EMcison, Xlumena Inc., MaunaKea, Apollo Endosurgery, ASPIRE Bariatrics, GIDynamics and MI Tech. He is a consultant for Boston Scientific and Xlumena Inc. Amrita Sethi is a consultant for Boston Scientific. All other authors have no financial conflicts of interest.