INTRODUCTION

In ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease (PD), existing medical therapy, including levodopa component preparation, may not be effective enough. In 1988, it was reported that consecutive administration of levodopa using a nasoduodenal tube to a treatment-resistant PD patient was effective against motor fluctuations [1]. Levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG, Duodopa┬«; AbbVie GK, Tokyo, Japan) administration to the small intestine by a gastrostomy infusion system was approved for the first time in Sweden in 2005. Delivery by percutaneous endoscopic gastrojejunostomy (PEG-J) provides more stable plasma levels and improves control of PD [2]. It has been increasingly performed in PD patients since it is therapeutically effective, relatively safe and easy to perform, simple to construct, and does not need periodic replacement. Since then, it has been approved in 48 countries including France, Germany, the UK, and the USA (as of June 2016). However, there is a non-negligible risk of adverse events (AEs) in association with the gastrostomy infusion system. Cheron et al. reported that the overall complication rates of PEG-J were 41% and 59% for immediate AEs (<24 h) and delayed AEs (0.1ŌĆō74 months), respectively [3]. Epstein et al. reported that 42% of AEs occurred during the first 4 weeks [4]. Although most were minor complications such as site infection, irritation, and peristomal leakage after successful gastrostomy tube placement, severe complications were rarely reported.

Here we report a case of a rare, severe complication of PEG-J, in which the tube migrated into the colon, with small intestinal telescoping.

CASE REPORT

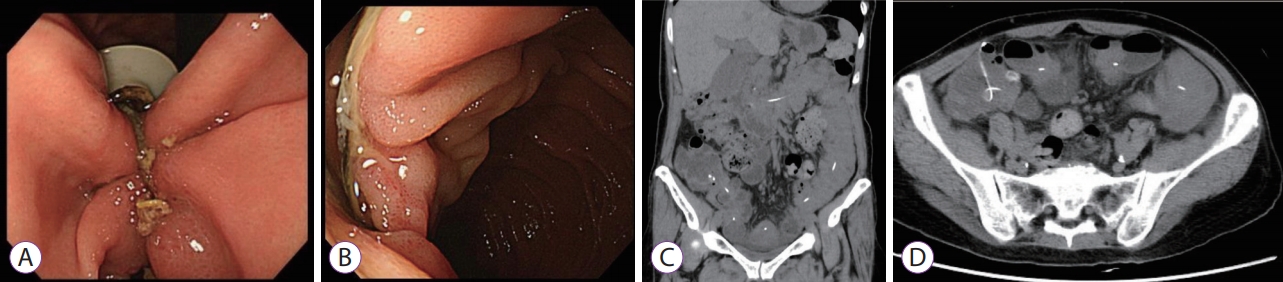

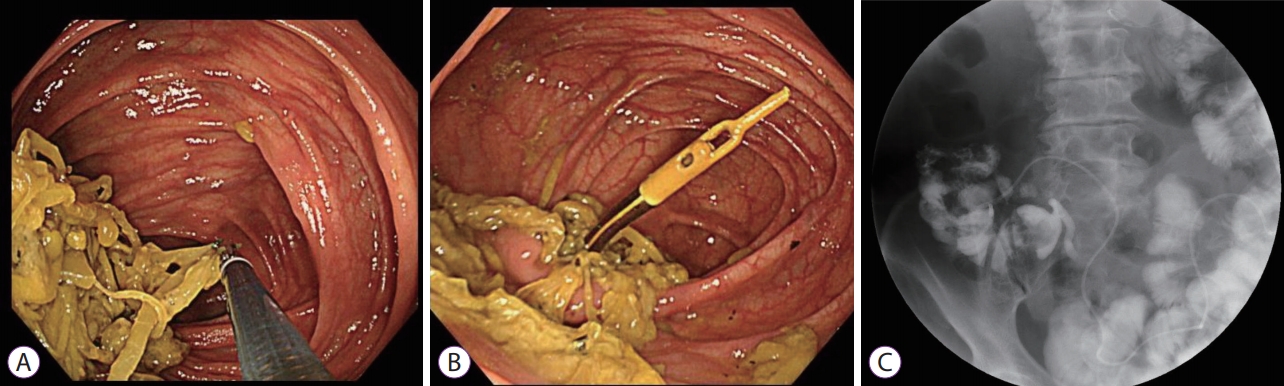

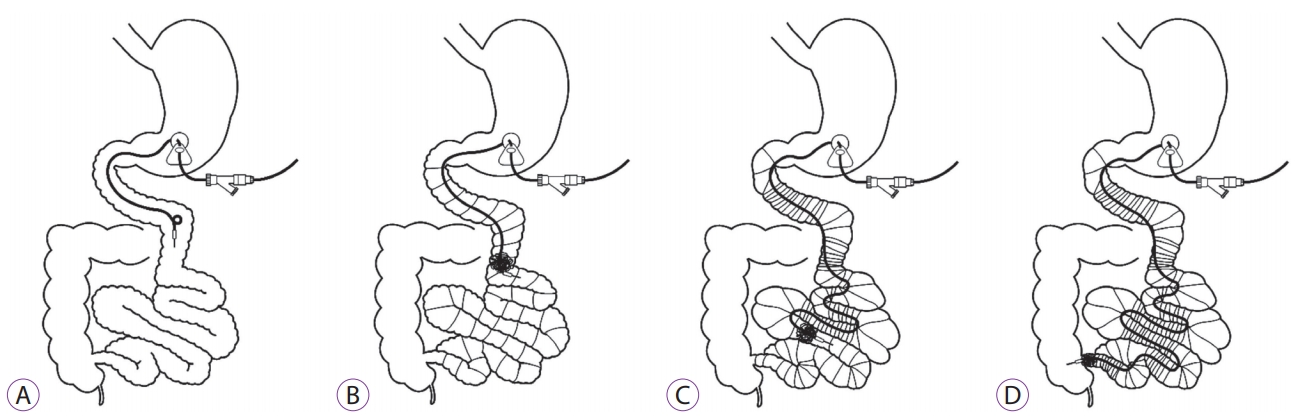

A 72-year-old woman with a 7-year history of advanced PD underwent PEG-J using the Duodopa system with the pull technique at the anterior wall of the lower gastric body (Fig. 1A). It was confirmed that the tip of the PEG-J tube was over the ligament of Treitz by contrast examination (Fig. 1B). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed normal findings in the stomach and duodenum, and no technical difficulties or immediate post-procedural complications were encountered. Her PD symptoms improved, with remarkable reduction of the ŌĆ£off ŌĆØ time, as well as improvement of motor symptoms (Unified ParkinsonŌĆÖs Disease Rating Scale motor scores were 23 before and 13 after LCIG). Three months after initial PEG-J tube placement, the patient developed abdominal pain and vomiting; however, there was no obvious abnormality in the administration flow rate of the LCIG and on the visible part of the tube EGD. and radiographic examination showed a longitudinal ulcer extending from the lower gastric body to the ileum end, with shortening of the gastric antrum that was being pulled down by the tube and small intestinal telescoping (Fig. 2A, B). Computed tomography showed small intestinal telescoping and the tube tip that reached the ileocecum (Fig. 2C, D). Colonoscopy showed a large bezoar (6 cm ├Ś 2 cm) that was attached around the tube tip, reaching the ascending colon (Fig. 3A, B). The bezoar, formed by persistent infusion of LCIG gel and food residues around the PEG-J tube tip, may have worked as an anchor. As a result, the gastric antrum and small intestine were shortened with telescoping (Fig. 4). It was impossible to remove the PEG-J tube from the body surface side; therefore, the PEG-J tube was cut in the body surface side and removed transanally by crushing the bezoar with forceps under colonoscopy. The patient resumed eating a few days after this procedure without any clinical AEs.

DISCUSSION

Patients with advanced PD and disabling motor fluctuations for whom optimized oral or transdermal PD medications are ineffective experienced a great improvement in their quality of life after the introduction of LCIG. Although PEG-J-related late complications, namely a bezoar and migration of the PEG-J tube, have previously been published [5,6], migration of the PEG-J tube in the colon with telescoping of the entire small intestine does not appear to have been reported previously.

Excessive traction on the stomach, duodenum, jejunum, and ileum by the PEG-J tube was considered the main reason for tube migration. Excessive traction on the stomach usually causes buried bumper syndrome; however, in this case migration of the PEG-J tube in the colon with telescoping of the entire small intestine occurred. Several factors may have contributed to this outcome. Firstly, the management of PEG-J tubes was not sufficiently diligent. It is not necessary to periodically exchange PEG-J tubes with LCIG infusion into the small intestine. In this case, the tubes were not changed, and there was no follow-up for up to 3 months after the initial procedure. In leaving the tube unchanged, a large bezoar formed by the accumulation of gel and food residues around the tube, from the tip to the loop, may have worked as an anchor. This resulted in long-term excessive traction by the PEG-J tube against the gastric and small intestinal walls, resulting in shortening of the small intestine with telescoping. Secondly, PD improvement may have contributed to migration of the PEG-J tube. Because PD patients usually show a decrease in gastrointestinal peristalsis [7], LCIG may ironically improve the motility of the small intestine, resulting in migration of the tube tip. Thirdly, a dietary fiber-rich meal may be a risk factor for bezoar formation. Constipation is one of the non-motor symptoms of PD, and the patient is typically encouraged to have dietary fiber-rich meals. Therefore, several cases of bezoars occurring after PEG-J construction have been reported. Marano reported duodenal occlusion with a food bezoar at the catheter tip, and perforation and fistula formation by mechanical stimulation of the small intestinal loop formation have been reported [8]. Lastly, the tube of the LCIG system is soft, and its pliability might have played a role in the migration of the tube tip into the colon. These considerations imply that in patients undergoing PEG-J, careful confirmation of the tube position and periodic replacements are important.

In conclusion, migration of a PEG-J tube for infusion of LCIG into the colon with telescoping of the small intestine can occur as a rare, late complication of PEG-J tube placement. This indicates that a fiber-free diet and periodic exchanges of the PEG-J tube by EGD could prevent this complication. In the future, it will be necessary to examine the appropriate exchange distance and improve the shape and materials of the tip of the tube to prevent the build-up of food residues. To date, this is the first report on such a complication of this procedure.