Korean Guidelines for Postpolypectomy Colonoscopy Surveillance

Article information

Abstract

Postpolypectomy surveillance has become a major indication for colonoscopy as a result of increased use of screening colonoscopy in Korea. In this report, a careful analytic approach was used to address all available evidences to delineate the predictors for advanced neoplasia at surveillance colonoscopy and we elucidated the high risk findings of the index colonoscopy as follows: 3 or more adenomas, any adenoma larger than 10 mm, any tubulovillous or villous adenoma, any adenoma with high-grade dysplasia, and any serrated polyps larger than 10 mm. Surveillance colonoscopy should be performed five years after the index colonoscopy for those without any high-risk findings and three years after the index colonoscopy for those with one or more high risk findings. However, the surveillance interval can be shortened considering the quality of the index colonoscopy, the completeness of polypectomy, the patient's general condition, and family and medical history.

INTRODUCTION

The detection and removal of colorectal polyps using colonoscopy is the most effective method of preventing colorectal cancer (CRC) and CRC-related deaths.1-5 Patients who have undergone colonoscopic polypectomy are at an increased risk for CRC and should be placed in a postpolypectomy surveillance program.2,3,6-11 Postpolypectomy surveillance has become a major component of endoscopic practice because an increasing number of patients with colorectal polyps have been discovered as a result of increased use of CRC screening, particularly the dramatic increase in screening colonoscopies.12,13 How-ever, although postpolypectomy colonoscopy surveillance could reduce the incidence of CRC and improve CRC-related mortality, its preventative effect is smaller than that of screening colonoscopies, and there is a need to increase the efficiency of surveillance colonoscopy practices and decrease the number of unnecessary examinations and their associated costs, risks, and the diversion of scarce medical resources.6,9,14

To this end, postpolypectomy surveillance guidelines have been established and revised in several Western countries.15-21 Although the incidence of CRC and its precursor, colorectal polyps, in South Korea is comparable to those in Western countries,22,23 Korea-specific practical guidelines for postpolypectomy surveillance are not currently available. Thus, there is a need for practical guidelines that reflect epidemiological characteristics of the Korean population and medical environment in Korea. To achieve this goal, the Korean Society of Gastroenterology (KSG), the Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (KSGE), the Korean Association for the Study of the Intestinal Diseases and the Korean Society of Abdominal Radiology organized a multi-society taskforce for a guideline for colorectal polyp screening, surveillance and management in order to review and analyze previous researches thus far and suggest the first Korean evidence-based practical guideline that can be used as a reference for postpolypectomy surveillance. However, this practical guideline cannot override the clinical judgments made by practicing physicians. In addition, this first Korean guideline should be revised and supplemented in the future as new evidences become available.

Purpose

The present guideline is designed as a patient care reference that will support physicians who are responsible for patients with colorectal polyps and for conducting colonoscopies in clinical practice. In the present report, a careful analytic approach was designed to address all of the available evidence in the literature that delineates predictors of advanced neoplasms, both cancers and advanced adenomas, with the aim of risk stratifying patients based on their index colonoscopy. However, the available Korean studies were not sufficient; therefore, expert opinions were collected using an internet survey and a Delphi meeting to represent the characteristics of the Korean population and the medical environment in Korea.

Necessity

Asymptomatic persons aged 50 years or older who are concerned about the possible presence of CRC are advised to receive CRC screening colonoscopies. Because the risk of future CRC is increased in patients who have undergone polyp removal, it is recommended that these patients participate in a periodic surveillance program.15,16,18-20,24 Korean society is aging rapidly, according to the population forecasts of the Korean Na-tional Statistical Office. The proportion of the population aged 50 or over (i.e., the population that may require CRC screening colonoscopies) is expected to rapidly increase from 29% in 2010 to 40% in 2020, and to 60% in 2050,25 but the number of experts and facilities available to conduct colonoscopies cannot increase indefinitely. Therefore, to make efficient use of limited medical resources, surveillance colonoscopy intervals should be scheduled so as to shift available resources from intensive surveillance to screening. This effort can also prevent the increase in medical expenditures and complications associated with unnecessary surveillance.

Limitations

Most of the systematically identified studies used as evidence in the present report were performed in Western countries, and the number of studies performed in Korea was limited. Therefore, the taskforce undertook web-based surveys to ascertain current Korean clinical practices and a Delphi meeting with clinical experts to explore the level of agreement on the initial practical guideline proposal. In addition, because most of the studies used evidence from observational studies rather than randomized controlled trials, the quality of evidence for this guideline was generally graded as low.

Guideline development teams and development processes

To develop this guideline, a multi-society taskforce consisting of experts recommended by the KSG, the KSGE, the Korean Association for the Study of the Intestinal Diseases and the Korean Society of Abdominal Radiology was established in June 2010. There were no conflicts of interest for any of the participating members.

Distribution of the guideline and implementing activities

The developed guideline will be co-published in the journals of the KSG, the KSGE, the Korean Association for the Study of Intestinal Disease (KASID) and the Journal of the Korean Society of Radiology. The guideline will also be published th-rough the websites of the relevant societies and in major medical newspapers. Additionally, the contents will be widely distributed through a summary guidebook to training hospitals.

Feedback after the guideline implementation and revisions

After a certain amount of time has passed after the distribution and implementation of the guidelines, adherence to the guideline in clinical practice will be assessed. Furthermore, the contents will be periodically revised to reflect the latest clinical knowledge.

METHODS

Definitions

The medical terms related to colonoscopic surveillance in this guideline were chosen to be consistent with the terms used in previous studies.

1) Postpolypectomy surveillance: Periodic examination of the colon to detect synchronous or metachronous neoplasia after polypectomy. This term does not include the use of colonoscopy or other procedures to monitor for polyp or cancer recurrence following a diagnosis of CRC.

2) Advanced adenoma: An adenoma of 10 mm or larger, an adenoma with high-grade dysplasia, or an adenoma containing 25% or more villous components.

3) Advanced neoplasia: An advanced adenoma or invasive cancer.

4) Index colonoscopy: The colonoscopy conducted most recently prior to the surveillance colonoscopy. The index colonoscopy should be performed according to the quality guideline of CRC screening recommended by the Ministry of Health and Walfare.26

5) Index adenoma: The largest adenoma found in an index colonoscopy. If all of the adenomas are smaller than 10 mm, the index adenoma refers to any adenoma that contains high-grade dysplasia or 25% or more villous components.

Although the incidence of CRC and CRC-related mortality are ideal outcome measures for evaluating the effectiveness of postpolypectomy surveillance, they are not practical to use because they require lengthy follow-up. Thus, advanced neoplasia, which includes both advanced adenoma and invasive cancer, has commonly been adopted as a surrogate biological marker for CRC.1,21

Key questions

The following key questions were selected for constructing postpolypectomy colonoscopic surveillance guidelines. 1) What are the risk factors for subsequent advanced neoplasia that must be considered when determining the colonoscopy surveillance interval? 2) Based on these risk factors, how can patients with a high risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia be identified? 3) What is the optimal colonoscopy surveillance interval in patients without risk factors for subsequent advanced neoplasia? 4) What is the optimal colonoscopy surveillance interval in patients with a high risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia?

Literature search

The literature review process began with a systematic MEDLINE, Cochrane Library and National Guideline Clearinghouse search for guidelines addressing surveillance colonoscopy after endoscopic resection of colorectal polyps that were published between 2000 and 2010. Both the postpolypectomy colonoscopic surveillance guidelines of the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer and the American Cancer Society (USMSTF-ACS)21 and the European Panel on the Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines for surveillance after colorectal polyp and CRC excision15 included evidence tables. The studies included in these evidence tables were reviewed.

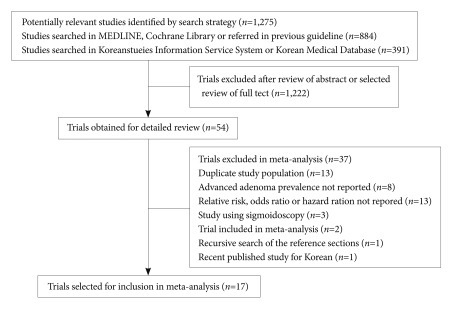

For the systematic literature review, electronic databases, including MEDLINE and the Cochrane Library, were searched from January 2000 and September 2010 to identify potentially relevant English-language articles. The keywords used in the English searches were "colonoscopy" AND "colon OR colonic OR colorecta" AND "polyp OR neoplasm OR neoplasia." Studies that were published in Korean were identified using the Korean Studies Information Service System (http://kiss.kstudy.com) and the Korean Medical Database (http://kmbase.medric.or.kr). The keywords used in Korean literature searches were "colonoscopy" AND "colorectal polyp" or "colonoscopy" AND "large intestinal polyps." The studies were included if they met the following criteria: 1) the manuscript was written in Korean or English; 2) the full manuscript was available; 3) the study was published between 1991 and 2010; 4) a cohort study, randomized controlled trial and pooled analysis study design was used; 5) the study participants were 18 years old or older with at least one colorectal polyp; 6) the intervention was defined as surveillance colonoscopy conducted for 6 months or longer after the index colonoscopy; and 7) the results included the incidence of subsequent advanced neoplasia at the surveillance colonoscopy, risk factors for subsequent advanced neoplasia, and colonoscopic surveillance interval. The studies conducted on patients with Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis CRC), familial polyposis, inflammatory bowel disease or CRC were excluded. The eligible articles were independently reviewed by the two taskforce members (H.S.N. and Y.D.H.). A total of 884 English references and 391 Korean references were identified using this search strategy. The article abstracts were individually evaluated for inclusion. The complete texts were obtained for the articles that were deemed potentially relevant. In addition, a manual recursive search of the reference sections of the selected studies was performed to identify other potentially relevant articles. In total, 833 English articles and 389 Korean articles were excluded from the initial literature pool, and the remaining 51 English articles and 3 Korean articles were selected for inclusion. The full manuscripts of these papers were reviewed in detail to prepare a standardized evidence table corresponding to the key questions outlined above. When the full manuscripts of the papers were reviewed, one additional paper that met the literature selection criteria was found in the cited references and was included in the selected literature after its full text was reviewed. In addition, a large-scale prospective cohort study conducted with a Korean population was published after the search period; this study was included in the selected literature (Fig. 1).

Meta-analysis

Among the reviewed studies, 17 presented the adjusted odds ratio (OR), adjusted relative risk (RR) or hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for one or more of the risk factors for subsequent advanced neoplasia during postpolypectomy colonoscopic surveillance and were included in a meta-analysis (Supplementary Table 1 online). Since pooled analysis is a study that is provided with unprocessed data from the individual studies, a pooled analysis was included in the meta-analysis, whereas individual studies were excluded from the meta-analysis. The studies that were initially designed as randomized controlled trials but lost the randomized effect when the data were extracted (because the case group and the control group were considered as a single cohort) were evaluated as observational studies. Because clinical heterogeneity in the study subjects, study designs, periods of colonoscopic surveillance and endpoint definitions was present among the studies selected for the meta-analysis, a random-effects model was applied. The pooled estimates were calculated using the inverse variance weighted estimation method to measure efficacy. Because RRs are evaluated more conservatively in effects estimations than in ORs, and because they are close to ORs in cases where disease prevalences are low, the results were presented as pooled estimated ORs for the studies that presented adjusted ORs and adjusted RRs27 and as pooled estimated HRs for the studies that reported HRs that were statistically analyzed in terms of time to the occurrence of the event. The results of the Cochran's Q-test indicated that the data were statistically heterogeneous (p<0.1). The meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager version 5.1 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK)

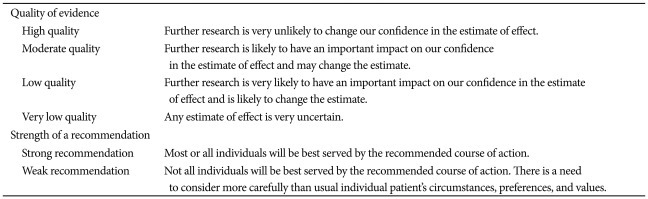

Quality of evidence and strength of recommendations

Recommendations are presented based on a systematic review of the selected literature and meta-analyses. The quality of evidence, indicating the degree to which each recommendation has scientific evidence, and the strength of the recommendations were determined following the methodology proposed by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group (Table 1).28,29

The quality of evidence was assessed to be "high" when evidence consisted of randomized controlled trials and "low" in cases where evidence included observational studies. However, in cases where studies used as evidence had limitations in the study design or execution, inconsistent results, indirect evidence, imprecise results or publication bias, the quality of evidence was adjusted downward. In cases of observational studies where large effects were observed, where reported effects might have been reduced due to confounding variables or where dose-response gradients existed, the quality of evidence was adjusted upward. The strength of each recommendation was assessed as "strong" or "weak" by considering the balance of desirable and undesirable consequences, the quality of the evidence, the confidence in the values and the references and the effective allocation of medical expenses and resources. That is, in cases where it was judged that following a specific recommendation would lead to significant health benefits or losses for most patients, the strength of the recommendation was classified as "strong." The strength of the recommendation was classified as "weak" in cases where it was judged that following the recommendation would lead to important benefits or loss in terms of the quality of the health of patients but where differences existed among patients, thus leading to the need to consider individual environments, preferences and values.28,29

POSTPOLYPECTOMY COLONOSCOPIC SURVEILLANCE GUIDELINES

The colonoscopy surveillance intervals recommended in this postpolypectomy colonoscopic surveillance guideline were determined according to an evaluation of the risk factors for subsequent advanced neoplasia, including the characteristics of the polyps found in the index colonoscopy and other patient characteristics:

The risk factors for subsequent advanced neoplasia

Does the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia increase depending on the number of adenomas in the index colonoscopy?

Patients with three or more adenomas have an increased risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia.

Quality of evidence: high

Level of agreement: completely agree (74%), generally agree (24%), partially agree (3%), generally disagree (0%), and totally disagree (0%)

Nine observational studies, including one pooled analysis30 and two Korean studies,9,10,30-36 evaluated the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia based on the number of adenomas found in the index colonoscopy (Supplementary Table 2 online). Although statistical heterogeneity among the studies existed, the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia increased when the number of adenomas increased, with a pooled OR of 1.93 (95% CI, 1.51 to 2.45) and a pooled HR of 2.20 (95% CI, 1.49 to 2.90) (Fig. 2.1.1, 2.2.1). Although the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia did not significantly increase in the patients with ≥2 adenomas compared to the patients with one adenoma (pooled OR, 2.18; 95% CI, 0.86 to 5.54) (Fig. 2.1.2),32,33 the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia significantly increased in the patients diagnosed with ≥3 adenomas, with a pooled OR of 2.84 (95% CI, 1.26 to 6.39) and a pooled HR of 2.20 (95% CI, 1.40 to 3.46) (Fig. 2.1.3, 2.2.2).

Forest plot for the number of colorectal adenomas as a risk factor for advanced neoplasia. CI, confidence interval.

Similar to the results of the meta-analysis, the patients in a Korean prospective cohort study with ≥3 adenomas showed an increased risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia, with an adjusted HR of 3.06 (95% CI, 1.51 to 6.57), compared with the patients diagnosed with ≥2 adenomas.36 A pooled analysis of eight large-scale North American randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies showed that the number of adenomas found in the index colonoscopy, along with patient age, was the most significant factor predicting the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia.30 A dose-response relationship between the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia and the number of adenomas was observed (p for trend <0.0001).30 When the number of adenomas diagnosed in the index colonoscopy was ≥5, the OR of the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia increased to 3.87 (95% CI, 2.76 to 5.42).30 Another meta-analysis analyzed 4 randomized controlled trials in which the surveillance colonoscopy was conducted at 3 years. Similar to the results of the present analysis, the pooled RR for the recurrence of advanced neoplasms at 3 years in the patients with ≥3 adenomas was 2.52 (95% CI, 1.07 to 5.97) with respect to that of the patients with 1 to 2 adenomas.37

By contrast, several studies have reported that polyp miss rates significantly increase as the number of polyps found in the index colonoscopy increases.38-42 Kim et al.41 have reported that the risk of missing polyps increased significantly in patients with ≥5 polyps, with an OR of 4.48 (95% CI, 1.91 to 10.5). However, most of the missed polyps were non-advanced adenomas or non-neoplastic polyps.39,42-45 Therefore, when a high-quality colonoscopy is performed, a long interval will be required for any of the missed polyps to become malignant.46-48

In addition, previously published guidelines have recommended shortening the colonoscopy surveillance interval in patients with multiple polyps. The British Society of Gastroenterology/Association of Coloproctology for Great Britain and Ireland recommends performing a surveillance colonoscopy at 1 year in patients with ≥5 adenomas or ≥3 adenomas including at least one that is ≥1 cm,17 and the USMSTF-ACS recommends conducting a surveillance colonoscopy within 3 years in patients with ≥10 adenomas.21

Does the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia increase depending on the size of the index adenoma(s)?

Patients with an adenoma that is 1 cm or larger have an increased risk of advanced neoplasia.

Quality of evidence: moderate

Level of agreement: completely agree (59%), generally agree (35%), partially agree (5%), generally disagree (0%), and totally disagree (0%)

Eight observational studies, including one pooled analysis30 and one Korean study, have evaluated the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia based on the sizes of the index adenomas (Supplementary Table 3 online).9,10,31,32,34-36,49 In most studies, the polyp size was evaluated during colonoscopy.6,31,49-53 Although statistical heterogeneity existed among the studies, the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia increased as the sizes of index adenomas increased, with a pooled OR of 1.78 (95% CI, 1.34 to 2.37) (Fig. 3.1.1). Although the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia did not significantly increase in the patients with 5 to 10 mm adenomas compared to the patients with ≤5 mm adenomas (pooled OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.96 to 1.43) (Fig. 3.1.2),9,30 the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia significantly increased in the patients with ≥10 mm adenomas compared to the patients with <10 mm adenomas (Fig. 3.1.3, 3.2.1), with a pooled OR of 1.59 (95% CI, 1.04 to 2.43) and a pooled HR of 2.04 (95% CI, 1.10 to 3.80).

Forest plot for the size of colorectal adenomas as a risk factor for advanced neoplasia. CI, confidence interval.

Similar results have been found in a Korean prospective cohort study in which the HR of the subsequent advanced neoplasia in the patients with ≥10 mm adenomas was 3.02 (95% CI, 1.80 to 5.06).36 In a pooled analysis by Martinez et al.,30 the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia increased as the sizes of the adenomas increased (p for trend <0.0001).

Large adenomas have an increased probability of containing areas with advanced histology, including villous or high-grade dysplasia and carcinoma. Previous studies have reported that the likelihood of a ≥20 mm adenoma containing an area of carcinoma may be as high as 32%.54,55 Large (20 mm or larger) sessile polyps are difficult to remove en bloc using traditional snare polypectomy. Although they can be resected en bloc using endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), ESD requires skilled endoscopists and is associated with serious complications, including perforation rates as high as 6.2% to 10%.55-57 Therefore, large sessile polyps are often removed using a piecemeal method in clinical practice.56,57 When piecemeal resection has been conducted, however, it is impossible to pathologically assess if there has been complete resection, and local recurrences in regions where polyps have been resected are reported to be as high as 12% to 55%.55,58-61 Therefore, current guidelines recommend that patients with large sessile adenomas that have been removed by the piecemeal method should be considered for follow-up evaluations in 2 to 6 months to verify complete removal.15-18,21

Is the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia greater in patients with tubulovillous or villous adenomas than in patients with tubular adenomas only?

Patients with tubulovillous or villous adenomas have an increased risk of advanced neoplasia.

Quality of evidence: low

Level of agreement: completely agree (26%), generally agree (53%), partially agree (16%), generally disagree (5%), and totally disagree (0%)

Seven observational studies, including one pooled analysis30 and one Korean study, assessed the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia after tubulovillous or villous adenoma resection (Supplementary Table 4 online).9,10,31,34,36,49,62 In most of these studies, a tubulovillous or villous adenoma was defined as a case in which the villous components in the index adenoma exceeded 20% to 25%. A meta-analysis showed that patients with tubulovillous or villous adenomas have a greater risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia than do patients with only tubular adenomas, with a pooled OR of 1.51 (95% CI, 1.16 to 1.97) and pooled HR of 1.83 (95% CI, 1.15 to 2.89) (Fig. 4).

Forest plot for villous/tubulovillous adenomas as a risk factor for advanced neoplasia. CI, confidence interval, TA, tubular adenoma.

In a Korean prospective cohort studies, by contrast, the patients with villous or tubulovillous adenomas did not have an increased risk of subsequent advanced adenoma (HR, 1.48; 95% CI, 0.74 to 2.95).36 In a Chinese population-based study using sigmoidoscopy, the patients with tubulovillous or villous adenomas were found to be at increased risk for subsequent advanced neoplasia (OR, 8.1; 95% CI, 4.2 to 15.6).63 Bertario et al.10 and Martinez et al.51 have separately assessed the risks of subsequent advanced neoplasia in patients with tubulovillous adenomas and villous adenomas and compared their risk to that of patients with only tubular adenomas. These authors did not find any significant differences in the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia.

Is the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia increased in patients with high-grade dysplasia adenomas compared with patients with low-grade dysplasia adenomas?

Patients with high-grade dysplasia adenomas have an increased risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia.

Quality of evidence: low

Level of agreement: completely agree (34%), generally agree (55%), partially agree (11%), generally disagree (0%), and totally disagree (0%)

After Atkin et al.11 reported that patients with high-grade dysplasia adenomas had a higher risk of colon and rectal cancer in 1992, one pooled analysis and four observational studies9,10,35,49 have reported an association between the diagnosis of adenoma with high-grade dysplasia and the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia upon colonoscopic surveillance (Supplementary Table 5 online). A meta-analysis of these studies revealed that patients diagnosed with high-grade dysplasia adenomas in the index colonoscopy have increased risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia upon surveillance colonoscopy, with a pooled OR of 1.33 (95% CI, 0.85 to 2.09) (Fig. 5.1.1) and pooled HR of 1.69 (95% CI, 1.14 to 2.50) (Fig. 5.2.1).

Forest plot for adenomas with high grade dysplasia as a risk factor for advanced neoplasia. CI, confidence interval.

By contrast, a pooled analysis by Martinez et al.30 has shown that the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia in patients with high-grade dysplasia adenomas was not increased compared with patients with low-grade dysplasia adenomas (pooled OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.81 to 1.35), and a meta-analysis by Saini et al.37 has indicated that high-grade dysplasia was a significant risk factor for subsequent advanced adenoma (pooled RR, 1.84; 95% CI, 0.53 to 8.93).

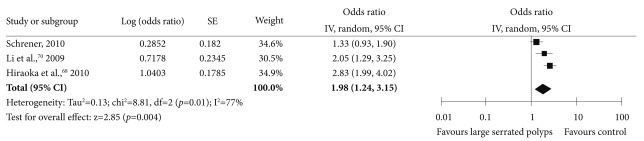

Does the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia increase in patients with serrated polyps?

Patients with serrated polyps 10 mm in size or larger have an increased risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia.

Quality of evidence: very low

Level of agreement: completely agree (3%), generally agree (61%), partially agree (34%), generally disagree (3%), and totally disagree (0%)

Serrated polyps are a heterogeneous group of lesions characterized by the glandular serration (that is, a "saw-toothed" architecture of the crypt epithelium).64 Historically, polyps with serrated architectures were thought to be a single entity (hyperplastic polyps) and were considered indolent, non-neoplastic, hyperproliferative lesions. Recently, there has been a growing recognition that there are different types of serrated polyps, including hyperplastic, sessile serrated adenomas, traditional serrated adenomas, and mixed adenomas, and that a small subset of these types may progress to invasive cancer through the novel "serrated pathway."65 CRC that develops via the serrated pathway is frequently located in the right colon, has high levels of microsatellite instability, and is associated with a CpG island methylator phenotype and mutation of the BRAF oncogene.66,67

In the systematic literature review, electronic databases (MEDLINE and the Cochrane Library) entries from January 2000 to September 2010 were searched to identify potentially relevant articles using "serrated" AND "polyp OR adenoma" as keywords. A total of 52 studies were found. Three observational studies assessed the risk of CRC in patients with serrated polyps ≥10 mm in size by assessing the coexistence of advanced neoplasia (Supplementary Table 6 online).68-70 In the meta-analysis of these studies, the patients with serrated polyps ≥10 mm in size had an increased risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia, with a pooled OR of 1.98 (95% CI, 1.24 to 3.15) (Fig. 6).

Forest plot of the large (≥10 mm) serrated polyps at index colonoscopy as a risk factor for advanced neoplasia. CI, confidence interval.

A previous pooled analysis of two randomized chemoprevention trials has indicated that the incidence of overall colo-rectal adenoma was not increased in surveillance colonoscopies performed 3 years after the removal of hyperplastic polyps.71 Based on this result, the risk of subsequent colorectal tumors in patients with only hyperplastic polyps was regarded to be the same as that of average-risk individuals who have never been diagnosed with colorectal polyps.15,17,21 However, Schreiner et al.69 have reported that the patients with right-sided, non-dysplastic serrated polyps, including hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated adenomas, have an increased risk of synchronous advanced adenomas (OR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.33 to 2.70) and subsequent adenomas (OR, 3.14; 95% CI, 1.59 to 6.20). Lu et al.72 have reported that a significant number of sessile serrated adenomas may not be accurately diagnosed in daily clinical practice and that these entities have a risk of progression to CRC. In addition, Lim et al.73 have reported that the presence of at least one hyperplastic polyp larger than 6 mm in either the proximal or distal colon was associated with an increased risk of advanced neoplasm (OR, 4.75; 95% CI, 2.30 to 9.78).

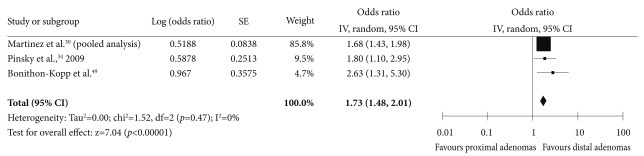

Locations of adenomas

The association between adenoma distribution and the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia has been recently evaluated in a pooled analysis30 and three observational studies (Supplementary Table 7 online).34,35,51 In all of these studies, the right colon was defined as all the segments proximal to the splenic flexure. The pooled OR of the risk for advanced neoplasia in the patients with any adenomas in the right colon compared to the patients with adenomas only in the left colon was 1.73 (95% CI, 1.48 to 2.01) (Fig. 7).

Forest plot for the location of index polyps as a risk factor for advanced neoplasia. CI, confidence interval.

Recent studies have suggested that right-sided colon cancer can develop through the serrated pathway.74,75 In addition, missed and recurrent adenomas are more likely to occur in the right colon.76 Therefore, recent studies have reported that colonoscopy is less effective in preventing right-sided colon cancers.77-79 However, right-sided colonic neoplasia was associated with specific patient characteristics, such as age and sex, and multiple environmental factors.80-84 Furthermore, right colonic adenomas were quite prevalent, and approximately 2/3 of the patients with any colorectal adenomas were reported as having at least one right side colonic adenoma.85 In the Delphi meetings, the level of agreement with the statement that adenomas located in the right colon are a risk factor for advanced neoplasia was inconsistent. Therefore, it is only tentatively concluded that right colonic adenomas are a risk factor for subsequent advanced neoplasia, and additional evidence is needed.

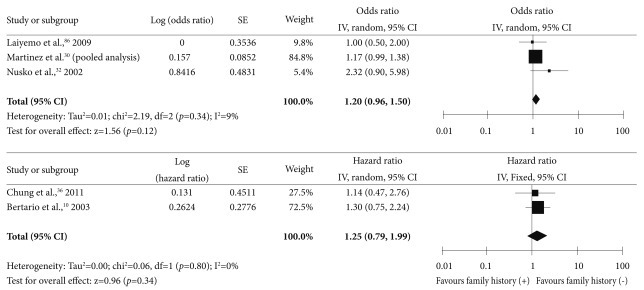

Patient age, sex, familial CRC history, smoking history and degree of obesity

The association between the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia and patient age has been evaluated in one pooled analysis30 and six observational studies.9,10,31,35,81,86 However, because these studies used different age group classifications, it was difficult to synthesize this information, and recommendations could not be drawn (Supplementary Table 8 online). While a pooled analysis by Martinez et al.30 has reported that the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia increased with age, Chung et al.36 have reported in a prospective Korean cohort study that patients aged 60 to 69 did not show a higher risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia than patients aged 50 to 59 (HR, 1.51; 95% CI, 0.86 to 2.65).

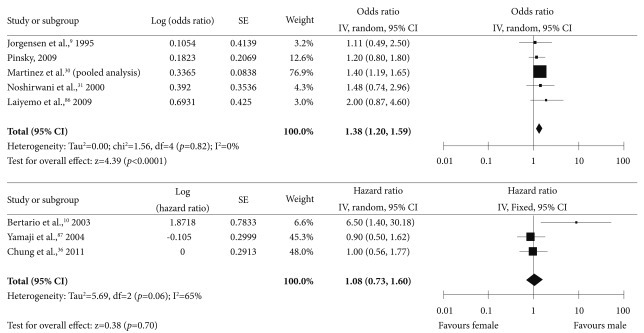

Several studies have assessed whether patient sex was associated with the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia (Supplementary Table 9 online).9,30,31,34,36,86,87 Although the pooled analysis by Martinez et al.30 has reported that the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia was greater in males, a Korean prospective cohort study showed no difference in the risk of advanced neoplasia between the sexes.36 Therefore, the evidence supporting different postpolypectomy surveillance policies based on patient sex is thought to be insufficient (Fig. 8).

Although a familial history of CRC was reported to have a positive association with the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia in some studies,32 a familial history of CRC was not associated with an increased risk of subsequent advanced adenoma in most studies (Supplementary Table 10 online).10,30,36,86 A meta-analysis of these studies showed a trend towards an increase, with a pooled OR of 1.20 (95% CI, 0.96 to 1.50), but this effect was not statistically significant (Fig. 9). In a Korean prospective cohort study, the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia was unchanged in the presence of a familial history of CRC (adjusted HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.57 to 1.77).36

Forest plot for the family history of colorectal cancers as a risk factor for advanced neoplasia. CI, confidence interval.

A limited number of studies have assessed the effects of smoking and obesity on the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia upon colonoscopic surveillance. In a pooled analysis by Martinez et al.30 and a Korean prospective cohort study, however, the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia did not increase with smoking (Supplementary Table 11 online) or with the degree of obesity, as assessed by body mass index (Supplementary Table 12 online).36

High-risk groups for subsequent advanced colorectal neoplasia at postpolypectomy surveillance

It is well known that the risk of subsequent colorectal adenoma and advanced neoplasia is increased in patients with polyps compared to patients without polyps.2,3,6-11 Identifying a high-risk group among postpolypectomy patients should thus be effective in establishing effective surveillance strategies and enhancing patient compliance to surveillance.15,21

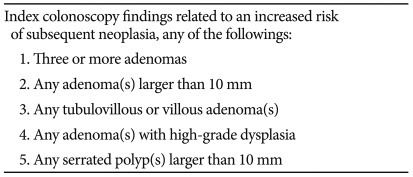

Based on the results of the systematic literature reviews and a meta-analysis, patients with any of the following index colonoscopy findings had an increased risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia: 1) 3 or more adenomas, 2) any adenoma larger than 10 mm, 3) any tubulovillous or villous adenoma, 4) any adenoma with high-grade dysplasia, and 5) any serrated polyps larger than 10 mm. Therefore, patients who exhibit any of these findings should be classified as being at high risk for subsequent advanced neoplasia for the purposes of postpolypectomy surveillance (Table 2).

The appropriate time interval for postpolypectomy surveillance colonoscopy

What is an appropriate time interval for postpolypectomy surveillance colonoscopy in patients without a high-risk finding at the index colonoscopy?

In patients without a high-risk finding at the index colonoscopy, surveillance colonoscopy should be performed five years after a high-quality index colonoscopy is administered by a qualified endoscopist. However, the surveillance interval can be shortened if the quality of the index colonoscopy was not high or if a high-risk finding was observed in a colonoscopy prior to the index colonoscopy.

Quality of evidence: low

Level of recommendation: weak

Level of agreement: completely agree (23%), generally agree (41%), partially agree (31%), generally disagree (5%), and totally disagree (0%)

In the 1990s and earlier, before there was sufficient evidence to recommend an appropriate postpolypectomy surveillance interval, surveillance colonoscopy was generally conducted on a yearly basis. The National Polyp Study was the first randomized controlled trial to address the question of an adequate postpolypectomy surveillance interval. In this study, 1,418 patients who had undergone removal of one or more adenomas were randomized into a two-examination group (with a surveillance colonoscopy at 1 year and 3 years) and a one-examination group (with a surveillance colonoscopy at 3 years). The percentage of patients with adenomas with advanced pathological features was the same in both groups (3.3%). Therefore, an interval of 3 years between colonoscopic adenoma removal and a surveillance colonoscopy to detect advanced neoplasia was suggested.6

In a large rigid sigmoidoscopy cohort study published in 1992, the patients with ≤10 mm tubular adenomas did not show an increased risk of subsequent CRC after polypectomy compared to the general population.11 In the Funen adenoma follow-up study, postpolypectomy patients randomly received surveillance at either 2 years or 4 years to assess the influence of these surveillance intervals on the risk of new colorectal neoplasms after the removal of pedunculated or small sessile tubular and tubulovillous adenomas. The cumulative incidence of advanced neoplasia in the group that received postpolypectomy surveillance at 4 years (5.2% [2.3% to 8.1%]) was not significantly different from that of the group that received surveillance at both 2 and 4 years (8.6% [3.8% to 13.3%]).9 These results suggest that patients who have undergone removal of one or two tubular adenomas of ≤10 mm should be considered to have a relatively low risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia and that the first surveillance colonoscopy after polypectomy may be delayed for three years or longer in these patients.

Lieberman et al.52 have described a randomized controlled trial of several intervals of surveillance colonoscopy after removing small (<10 mm) adenomas. The patients with tubular adenomas <10 mm were randomly assigned by concealed allocation to receive colonoscopic surveillance at 2 and 5 years (n=300) or at 5 years only (n=294). Both the groups had a similar risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia (4.9% for the 5-year group and 6.4% for the 2- and 5-year group; p=0.55).52 In a recent Korean prospective cohort study, the 5-year cumulative incidence rates of advanced adenoma in normal subjects (n=1,242) and in patients who had undergone removal of one or two small (<10 mm) tubular adenomas (n=671) were 2.4% and 2.0%, respectively. The risk of advanced neoplasia at 5 years after the removal of one or two small tubular adenomas was not increased compared to that of the normal subjects (adjusted HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.61 to 2.17).36

Currently, the intervals suggested for postpolypectomy surveillance colonoscopy are based on the findings from the index colonoscopy, i.e., the most recent high-quality colonoscopy. Recently, Robertson et al.88 have investigated the risk of clinically significant adenoma recurrence based on the results of 2 previous colonoscopies. This study was performed on patients with a qualifying adenoma at their first colonoscopy who then underwent second and third colonoscopies at roughly 3-year intervals. If the second examination showed no adenomas, then the results of the first examination added significant information about the probability of high-risk findings at the third examination (12.3% if the first examination had high-risk findings vs. 4.9% if the first examination had low-risk findings; p=0.015).88 Similarly, Laiyemo et al.86 have reported that the probability of detecting an advanced adenoma in the third colonoscopy was 13.8% in the polyp prevention trial participants with low-risk adenomas at the first colonoscopy and high-risk adenomas at the second colonoscopy and 11.9% in those with high-risk adenomas at the first colonoscopy and low-risk adenomas at the second colonoscopy. However, those authors also reported that the probability of detecting an advanced adenoma in the third colonoscopy was 6.8% in the participants with high-risk adenomas at the first colonoscopy but no adenomas at the second colonoscopy, which was lower than the rate reported by Robertson et al.88 These results suggest that both the index colonoscopy and the earlier colonoscopies should be considered when determining the appropriate surveillance interval. However, there is no further evidence to suggest an appropriate time interval for the third colonoscopy.

What is an appropriate time interval for postpolypectomy surveillance colonoscopy in high-risk groups?

In patients with a high risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia, surveillance colonoscopy should be performed three years after a high-quality index colonoscopy is administered by a qualified endoscopist. However, the surveillance interval can be shortened if the quality of the index colonoscopy was low or based on the index colonoscopy findings, the completeness of polyp removal, patient conditions, family history and medical history.

Quality of evidence: low

Strength of a recommendation: weak

Level of agreement: completely agree (21%), generally agree (44%), partially agree (23%), generally disagree (10%), and totally disagree (3%)

Most of the high-quality studies that have evaluated the risk factors for subsequent advanced neoplasia are observational studies conducted on participants in polyp prevention trials. Because these studies were conducted after the National Polyp Study and the Funen adenoma follow-up study, most of the polyp prevention trials have included a three- or four-year surveillance interval.10,30-32,34-36,49,51,87 Although the likelihood of detecting advanced adenomas in a surveillance conducted 3 or 4 years later was increased for the high-risk groups in these studies, the actual incidence of CRC was quite low. Therefore, three years may be suggested as an appropriate surveillance interval. However, the patients who participated in the National Polyp Study and other clinical trials received a high-quality colonoscopy from expert endoscopists or were checked for missed polyps and complete polyp resection in an additional clearing colonoscopy. In addition, some chemoprevention trials have excluded patients with a familial history of CRC. In clinical practice, therefore, detailed information about the quality of the index colonoscopy, patient family history and medical history should be considered along with the findings of the index colonoscopy to determine the optimal surveillance interval.

Furthermore, it has not yet been determined whether the risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia increases in patients with two or more overlapping high-risk findings. In a large-scale rigid sigmoidoscopy study by Atkin et al.,11 the standardized incidence ratio of CRC in the patients with a single high-risk adenoma in the index sigmoidoscopy was 2.9 (95% CI, 1.8 to 4.5), whereas that of the patients with multiple high-risk adenomas increased to 6.6 (95% CI, 3.3 to 11.8). Noshirwani et al.31 have reported that the probability of subsequent advanced adenomas in patients with three adenomas smaller than 10 mm at the index colonoscopy was estimated to be 8.5%, whereas the probability increased to 21.3% in those with three adenomas, at least one of which was ≥10 mm. This study also estimated that the probability of subsequent advanced adenoma at surveillance was 15.3% in the patients with four or more adenomas <10 mm and 34.5% in those with four or more adenomas and at least one ≥10 mm. These results suggest that overlapping high-risk findings further increase the risk of subsequent advanced adenoma. However, this evidence is insufficient to support any specific postpolypectomy surveillance guidelines.

DISCUSSION

Because patients with colorectal adenomas are at increased risk for subsequent colorectal neoplasia compared to patients with no polyps, periodic postpolypectomy colonoscopic surveillance is necessary.2,3,6-11 The index colonoscopy findings associated with an increased risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia at surveillance include the following: 1) the presence of 3 or more adenomas, 2) any adenomas ≥10 mm, 3) any tubulovillous or villous adenomas, 4) any adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, and 5) any serrated polyps ≥10 mm. It is suggested that patients with any of these conditions should be classified into an advanced neoplasia high-risk group at their subsequent postpolypectomy surveillance colonoscopies.

Based on the literature review and evidence, it is recommended that colonoscopic surveillance in Korea be performed 3 years after polypectomy in those patients with high-risk findings and 5 years after in those patients without high-risk findings.

However, several factors should be considered before determining the surveillance colonoscopy interval (Table 3). First, the index colonoscopy should reach the cecal base with adequate bowel preparation. If the cecal intubation failed or if bowel preparation was inadequate during the index colonoscopy, significant colorectal lesions may be missed, and a repeat colonoscopy is recommended.89 Because the quality of the index colonoscopy may vary significantly among endoscopists, screening and surveillance colonoscopies should only be conducted by qualified endoscopists.90-92 If any polyps, especially adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, may have been incompletely removed, the completeness of the resection should be confirmed by a repeat colonoscopy.55,58-61 Finally, the surveillance interval proposed in this guideline is applicable to asymptomatic adults. The necessity of a diagnostic colonoscopy in any symptomatic patients should be assessed by a physician, regardless of the recommended surveillance interval. In summary, physicians should determine the appropriate surveillance colonoscopy intervals for patients on a case-by-case basis, considering the quality and bowel preparation status of the index colonoscopy, the completeness of the adenoma resection, and the patient's general health, family history and medical history.

Previous guidelines have suggested short surveillance intervals of 1 to 3 years for patients with 10 or more adenomas. However, these recommendations have not been based on sufficient evidence.15,17-21 In patients with pathologically incompletely resected polyps or polyps that were resected in piecemeal fashion, by contrast, a follow-up colonoscopy within two to six months is recommended by most experts because of the risk of residual adenomatous lesion.18-21 However, no specific time interval for the follow-up colonoscopy in these patients could be suggested in this guideline because there is insufficient evidence to determine an appropriate surveillance interval. There is also insufficient evidence to suggest an appropriate surveillance interval in patients who have undergone multiple colonoscopies before the index colonoscopy or who exhibit multiple high-risk findings.

This is the first postpolypectomy surveillance guideline published for Korea. Because the Korean data on postpolypectomy surveillance were quite limited, many of these recommendations were made based on evidence from Western countries in which the health care environments are different from that of Korea. In particular, colonoscopy fees are lower in Korea than in Western countries; therefore, further cost-effectiveness analysis should be conducted using the results of colorectal polyp studies performed with Korean populations. Finally, it is emphasized that this guideline cannot address all clinical situations and thus cannot supersede clinical judgments that consider the specific characteristics of individual patients.

SUMMARY

Patients with three or more adenomas have an increased risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia.

Patients with an adenoma that is 1 cm or larger have an increased risk of advanced neoplasia. In cases where tubulovillous or villous adenomas have been found in the index colonoscopy, the risk of detecting advanced neoplasia in a surveillance colonoscopy is increased compared with the risk in patients with non-villous tubular adenomas.

Patients with tubulovillous or villous adenomas have an increased risk of advanced neoplasia.

Patients with high-grade dysplasia adenomas have an increased risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia.

Patients with serrated polyps 10 mm in size or larger have an increased risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia.

Patients should be considered at high risk for subsequent advanced neoplasia at surveillance colonoscopy when one or more of the following conditions have been detected at index colonoscopy: 1) 3 or more adenomas, 2) any adenoma larger than 10 mm, 3) any tubulovillous or villous adenoma, 4) any adenoma with high-grade dysplasia, and 5) any serrated polyps larger than 10 mm.

In patients without a high-risk finding at the index colonoscopy, surveillance colonoscopy should be performed five years after a high-quality index colonoscopy is administered by a qualified endoscopist. However, the surveillance interval can be shortened if the quality of the index colonoscopy was not high or if a high-risk finding was observed in a colonoscopy prior to the index colonoscopy.

In patients with a high risk of subsequent advanced neoplasia, surveillance colonoscopy should be performed three years after a high-quality index colonoscopy is administered by a qualified endoscopist. However, the surveillance interval can be shortened if the quality of the index colonoscopy was low or based on the index colonoscopy findings, the completeness of polyp removal, patient conditions, family history and medical history.

Acknowledgments

We extend profound thanks to Professor Chae, Hiun Suk (The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine), Professor Han, Dong Soo (Hanyang University Guri Hospital), and Professor Jeen, Yoon Tae (Korea University College of Medicine) who gave unsparing advice regarding the development of these guidelines for postpolypectomy surveillance.

We also give great thanks to the Korean Association of Internal Medicine and Korean Physicians Association for their agreement with final version of these guidelines.

This study was initiated with the support of the Korean Society of Gastroenterology, the Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and the Korean Association for the Study of Intestinal Disease. This study was supported by a grant for the Korean Health Technology R&D Project with the Ministry for Health and Welfare of the Republic of Korea (A102065-23).

Notes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

These guidelines are being co-published in the Korean Journal of Gastroenterology, the Intestinal Research, and the Clinical Endoscopy for the facilitated distribution.