The Role of Colonoscopy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Article information

Abstract

An endoscopic evaluation, particularly ileocolic mucosal and histological findings, is essential for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The introduction of antitumor necrosis factor agents has changed the therapeutic paradigm of patients with IBD, but an endoscopic evaluation is more important to guide therapeutic decision-making. In the future, endoscopy with a histological evaluation will be increasingly used in patients with IBD. Both Crohn colitis and ulcerative colitis result in an increased incidence of colorectal carcinoma. Thus, surveillance colonoscopy is important to detect early neoplastic lesions. Surveillance ileocolonoscopy has also changed recently from multiple random biopsies to pancolonic dye spraying with targeted biopsies of abnormal areas.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which is a heterogeneous group of diseases that can be broadly classified into Crohn disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic idiopathic inflammatory disorder affecting the gastrointestinal tract. Until the late 1990s, the therapeutic goal for IBD was clinical remission.1 However, the introduction of antitumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents has changed the IBD therapeutic paradigm. Accumulated evidence regarding anti-TNF agents in patients with IBD indicates that mucosal healing is an important therapeutic endpoint in clinical trials, and is also used in clinical practice.2 This altered therapeutic paradigm is changing the role of endoscopy in IBD. Additionally, improvements in endoscopy and other devices are changing the methods of assessing response to treatment and surveillance. Herein, we review the recent role of colonoscopy in IBD.

THE ROLE OF COLONOSCOPY IN IBD

Initial diagnosis

Endoscopy, particularly ileocolonoscopy, is the method of choice for initial diagnosis and assessment of the extent of bowel involvement. It allows classification of disease based on endoscopic extent, severity of mucosal disease, and histological features. It also allows an assessment of suspected stenoses in the distal ileum or colon.

The primary reason for endoscopy is to obtain tissue.3 The four histological criteria of IBD are: distortion in crypt architecture, pyloric metaplasia in the terminal ileum, Paneth cells in the left or distal colon, and basal cell plasmacytosis. These criteria define chronic inflammation and are necessary for IBD to be a considered. The presence of a granuloma is not necessary for the diagnosis of IBD. However, because a sarcoidlike granuloma is highly specific for CD, the presence of a granuloma has been used to distinguish between UC and CD.4

A full colonoscopy is rarely needed in cases of acute severe colitis and may be contraindicated.5 A rectal biopsy should be taken for histology even if there are no macroscopic changes. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy should be considered when dyspepsia coexists. However, the role of small bowel endoscopy remains to be defined.6

Evaluation of therapeutic effect

Mucosal healing on endoscopy is a key prognostic parameter in the management of IBD after introducing anti-TNF agents. Thus, the role of endoscopy for monitoring IBD activity has been highlighted.

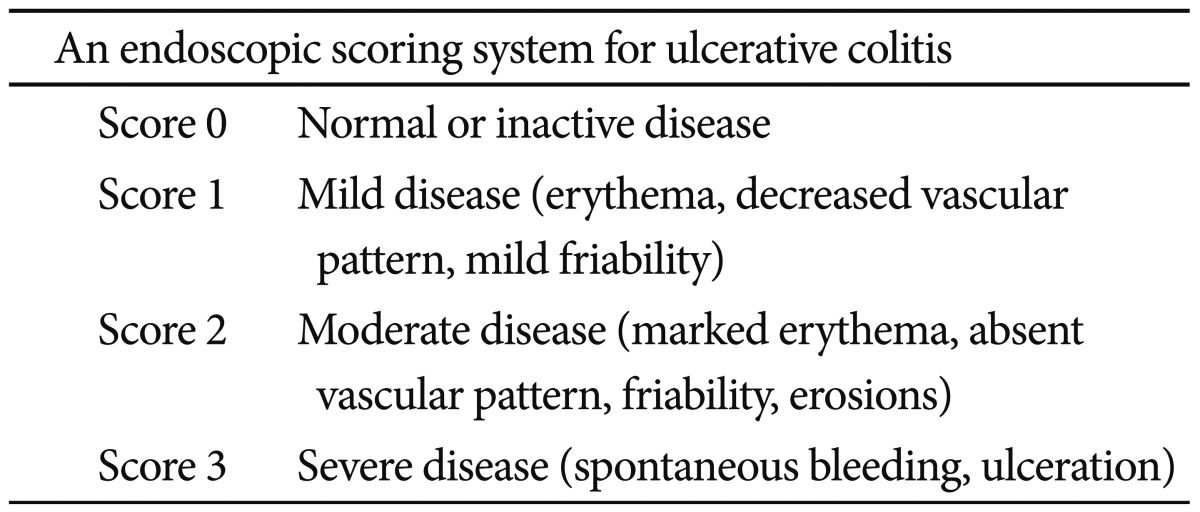

Mucosal healing is usually defined as the resolution of visible ulcers on endoscopy. However, no validated definition of mucosal healing exists with respect to endoscopic response or remission of either UC or CD. Mucosal healing has long been recognized as a therapeutic goal in patients with UC because UC is associated with only mucosal inflammation and affects the colon. Mucosal healing is generally defined by the Mayo Clinic endoscopy subscore of 0 (normal, or inactive), as presented in Table 1.7 Endoscopy subscores of 0 or 1 at week 8 have a significantly lower risk of colectomy over the next year, compared to patients with scores of 2 or 3 (p=0.0004). An endoscopy subscore of 0 at week 8 predicted symptom relief at weeks 30 and 54 in 71% and 74%, respectively, compared to 51% and 47% for a score of 1 at week 8. Patients with an endoscopy subscore of 0 at week 8 have a higher rate of steroid-free remission at week 54 than those with a score of 1.8 The mucosal findings on endoscopy, particularly proctosigmoidoscopy, in clinically improved patients with UC are important for therapeutic decision-making.9 Thus, endoscopy with a histological evaluation will be increasingly used in patients with UC.

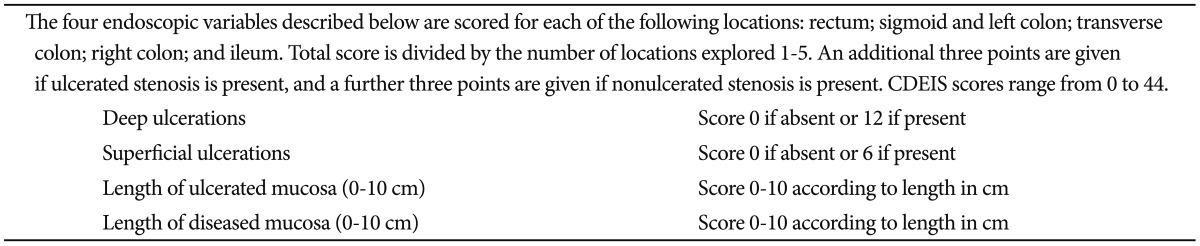

The Crohn's disease endoscopic index of severity (CDEIS) is the gold standard for assessing CD endoscopic activity (Table 2).10 Definitions of mucosal healing are generally based on the CDEIS, which is presented in Table 2.11 The threshold for endoscopic remission has been set as a CDEIS <6, with other criteria for response (a decrease in CDEIS >5), complete endoscopic remission (CDEIS <3), and mucosal healing (absence of ulcers). The prognosis of CD is independently affected by the presence of deep and extensive ulceration at index colonoscopy.12 Mucosal healing on ileocolonoscopy in patients with CD reduces the likelihood of clinical relapse, the risk of surgery, and hospitalization.13,14 Recently, deep remission has been suggested as a treatment goal in CD, following its use in rheumatoid arthritis.15 Deep remission includes not only symptom control, but also alteration of the biological processes that contribute to the disease, such as progressive structural damage and functional decline. Accomplishing deep remission might be a method of altering the course of CD. The Extend the Safety and Efficacy of Adalimumab through Endoscopic Healing trial empirically defined deep remission as a Crohn's Disease Activity Index <150 and complete mucosal healing.16 In the Stop Infliximab in Patients with Crohn's Disease trial, deep remission was defined as a CDEIS of 0, a calprotectin level >250 mg/g, and an high sensitivity C-reactive protein <5 mg/L.17 These emerging concepts in CD have included mucosal healing as an essential requirement. However, the definitions of deep remission have not been validated.

Ileocolonoscopy might not be enough to evaluate mucosal healing because CD can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract-from the mouth to the anus-and typically features transmural inflammation. Thus, transsectional imaging is needed to evaluate mucosal healing in cases of CD. A prospective study showed that the magnitude of various quantitative magnetic resonance imaging changes, such as wall thickening, contrast signal intensity, and relative contrast enhancement, are correlated with the severity of endoscopic lesions in patients with CD.18

Surveillance colonoscopy for colitic cancer

Both Crohn colitis and UC increase the incidence of colorectal carcinoma and the need for surveillance colonoscopy. Generally, the incidence of colorectal cancer in patients with UC is 2- to 5-fold higher than that in general population.19 It is widely accepted that patients with Crohn colitis, with a similar extent and duration of colonic involvement, have a similar risk to those with UC.20

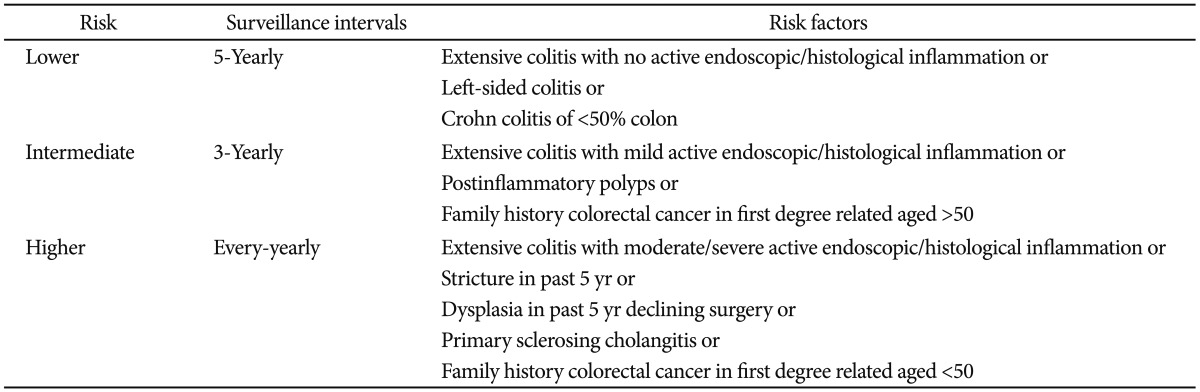

Surveillance colonoscopy is important to detect early neoplastic lesions. The surveillance intervals are stratified based on colitic cancer risk. The colitic cancer risk is estimated based on the duration and extent of colitis, coexistence of primary sclerosing cholangitis, family history of colorectal cancer, colonoscopic findings, and histological findings. The surveillance intervals are shown in Table 3.20,21 As surveillance colonoscopy becomes more critical in detection, the technique has evolved. Recently, pancolonic dye spraying or confocal microendoscopy with targeted biopsies of abnormal areas has been recommended.21 However, to use these newer colonoscopic techniques effectively, specialized training is needed. If chromoendoscopy is not used, multiple random biopsies should be taken at regular intervals.

CONCLUSIONS

Endoscopic evaluations for assessment of the response to treatment and for prediction of the course of IBD have remained controversial. An endoscopic examination with histological evaluation allows a careful objective surveillance for colorectal cancer. Endoscopic evaluation of the response to treatment is reasonable if the objective is to guide therapeutic decision-making. Chromoendoscopy with targeted biopsies of abnormal lesions is more appropriate than multiple random biopsies for colorectal cancer surveillance. Monitoring mucosal healing is promising. However, long-term follow-up, prospective studies of anti-TNF agents in patients with IBD are needed.

Notes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.