Electrohydraulic Lithotripsy of an Impacted Enterolith Causing Acute Afferent Loop Syndrome

Article information

Abstract

Afferent loop syndrome caused by an impacted enterolith is very rare, and endoscopic removal of the enterolith may be difficult if a stricture is present or the normal anatomy has been altered. Electrohydraulic lithotripsy is commonly used for endoscopic fragmentation of biliary and pancreatic duct stones. A 64-year-old man who had undergone subtotal gastrectomy and gastrojejunostomy presented with acute, severe abdominal pain for a duration of 2 hours. Initially, he was diagnosed with acute pancreatitis because of an elevated amylase level and pain, but was finally diagnosed with acute afferent loop syndrome when an impacted enterolith was identified by computed tomography. We successfully removed the enterolith using direct electrohydraulic lithotripsy conducted using a transparent cap-fitted endoscope without complications. We found that this procedure was therapeutically beneficial.

INTRODUCTION

Afferent loop syndrome (ALS) is characterized by the accumulation of bile acid and pancreatic juice, and distention due to obstruction of the duodenal or proximal jejunal afferent loop. ALS is a rare complication following Billroth II gastrojejunostomy, occurring in ~0.3% of patients.1 ALS may be caused by mechanical obstruction of the afferent loop by adhesions, internal hernias, volvulus, intussusception, intestinal kinks/strictures, and malignancy.2 Rarely, an impacted enterolith can be the cause of obstruction, and few such cases have been reported.3,4

Surgical intervention is often considered for the removal of an enterolith causing ALS. However, the outcome may be unsatisfactory if a patient is in poor general health. In such cases, peritoneal adhesions may develop. Alternatively, percutaneous enterostomy has been considered as a palliative method. However, maturation of the percutaneous tract can occur very slowly prior to the procedure, and may cause discomfort and pain. Endoscopic enterolith extraction has been associated with a poor success rate.5

We report a case of acute ALS caused by an enterolith, triggering acute pancreatitis, which was successfully managed via direct electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL) using a transparent cap-fitted endoscope.

CASE REPORT

A 64-year-old man visited our emergency room complaining of epigastric pain and vomiting. He had a history of subtotal gastrectomy, involving a Billroth II reconstruction to treat a peptic ulcer perforation, 25 years previously. He had also undergone endoscopic retrograde cholangiography and cholecystectomy to treat a common bile duct stone and cholecystitis 7 years ago. His vital signs at admission included a blood pressure of 110/70 mm Hg, pulse rate of 88 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute, and body temperature of 36.3℃. Physical examination revealed icteric sclera, abdominal distension, and tenderness in the epigastric area. On admission, his complete blood analysis included a hemoglobin concentration of 15.9 g/dL, leukocyte count of 37,470/mm3 (neutrophils 73%), and platelet count of 165,000/mm3. Blood chemistry was analyzed as a total serum bilirubin concentration of 3.2 mg/dL, creatinine of 1.1 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase of 664/240 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase of 190 IU/L, γ-glutamyltransferase of 552 IU/L, amylase of 2,528 µg/dL, and lipase of 3,032 IU/L. A plain radiograph of the abdomen revealed no abnormality and the gas pattern was also normal. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a 2.7×2.5×2.1 cm sized, oval heterogeneous high density lesion in a dilated afferent loop and a diffusely enlarged pancreas with peripancreatic hazy reticular infiltration into fatty tissue (Fig. 1).

(A) An axial abdominal computed tomography (CT) image showing a large impacted enterolith (arrow) in the dilated fluid-filled afferent loop. (B) Coronal CT reconstruction better demonstrating the afferent loop obstruction by the enterolith (arrow).

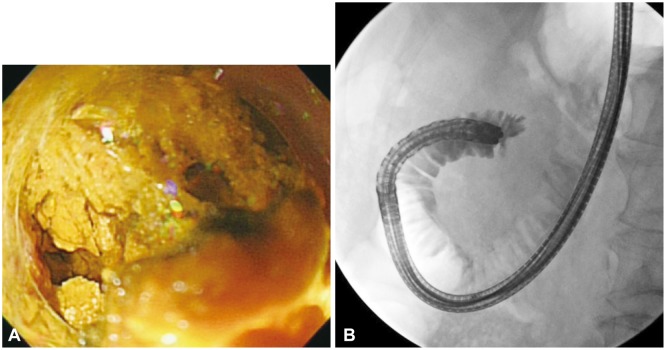

An emergency transparent cap-fitted endoscopy procedure was performed on the day of admission to obtain an accurate diagnosis. The site of anastomosis was intact and no stricture was evident. However, a very large yellowish enterolithic impaction was apparent in the distal afferent loop. Injected contrast material could not be passed through the afferent loop because of complete obstruction by the enterolith (Fig. 2). We attempted to remove the enterolith via EHL, employing direct cap-fitted endoscopy. A 3 Fr EHL probe was passed through the biopsy channel of the gastroscope. Next, we performed EHL using an electrohydraulic shock wave generator (Litho-tron EL-27; Olympus Optical, Hamburg, Germany) delivering shocks of increasing power (up to 500 mJ) at 2,000 V with continuous instillation of normal saline under direct endoscopic visualization. Endolith fragmentation was successful and a large fragment was removed by a retrieval net. Thereafter, a large active ulcerative lesion located on a blind pouch of the afferent loop, and an acute circular ulcerative lesion located at the site of stone removal was evident (Fig. 3). No immediate complications developed. Four days later, the patient underwent a second-look endoscopy procedure. There was no residual enterolith, although small ulcers on the proximal afferent loop caused by local pressure were apparent. The patient recovered from pancreatitis without any complications, and was discharged 16 days after the procedure.

(A) Endoscopically, an impacted yellow enterolith is apparent in the afferent loop. (B) Contrast material could not pass the obstruction due to the completely impacted enterolith on the fluoroscopic image.

DISCUSSION

ALS is a term used to describe symptoms caused by obstruction of the duodenal or proximal jejunal afferent loop. This complication usually occurs after previous partial gastrectomy and gastrojejunostomy. The clinical features of ALS are variable and depend on whether afferent loop obstruction is acute or chronic. Acute ALS usually occurs within 1 week after surgery and is accompanied by abrupt epigastric pain, vomiting, and acute clinical exacerbation. Chronic ALS usually occurs several months or years after surgery, accompanied by partial obstruction of the afferent loop and abdominal distension, which subsides (with bilious vomiting) 1 to 2 hours after a meal.6 Obstruction of the afferent bowel with ongoing accumulations of biliary, pancreatic, and intestinal secretions causes afferent loop dilatation. The symptoms of afferent loop obstruction are nonspecific, but back pressure from the dilated afferent loop can in rare cases cause biliary and gallbladder dilatation, and acute pancreatitis.

Most cases of ALS are caused by mechanical obstruction of the afferent loop by abdominal adhesions developing after surgery, internal hernias, intussusceptions, volvulus, anastomotic site strictures, cancer recurrence, and peritoneal metastasis.2 Obstruction of the afferent loop caused by an enterolith is very rare, and few cases have been reported.3,4 Enteroliths are stones that develop within the intestinal tract. Most enteroliths are usually encountered within diverticula, surgically created intestinal pouches or proximal to an obstruction in the small or large bowel.5 Enterolith formation is thought to be attributable to bowel hypomotility or stasis. Such stasis alters the bacterial flora and promotes bacterial growth. Bacteria may convert cholic acid to insoluble deoxycholic acid, and may also release glycine and taurine from bile salts. Precipitation of unconjugated bile acids within the bowel lumen leads to stone formation.7 Previously reported causes of enterolith formation in ALS have involved stagnation of intestinal flow caused by bowel dysmotility, and development of strictures and adhesions causing kinks.3 Flow stasis within the afferent loop caused by bowel hypomotility may trigger enterolith formation. It is also possible that biliary stones are occasionally extracted naturally into the afferent loop and slowly develop into large enteroliths.

In the present case, we thought that such a biliary stone had slowly increased in size, resulting in chronic large-scale ulceration of the blind pouch of the afferent loop. Next, acute migration of the enterolith to the distal region of the afferent loop triggered acute ALS associated with severe acute pancreatitis. We did not analyze the enterolith, and thus cannot state if the stone was truly an enterolith or rather a bezoar. However the patient's previous history of biliary stone formation and easy fragmentation by EHL may support such a hypothesis.

Clinical diagnosis of ALS can be difficult. Patients present with nonspecific symptoms and ALS is not associated with specific laboratory test findings in the absence of cholangitis or pancreatitis. Imaging studies are needed for definitive diagnosis. The CT appearance of ALS is highly characteristic, if not pathognomonic. Thus, CT is the imaging modality of choice and can also determine the site, extent, and cause of ALS.8 In the present case, CT was performed to confirm acute pancreatitis because our patient complained of acute abdominal pain and both blood amylase and lipase levels were elevated. Abdominal CT revealed acute pancreatitis, a fluid-filled dilated afferent loop, a large oval hypodense mass suggestive of an enterolith, and biliary tract dilatation. We believe that back pressure from the dilated afferent loop by an enterolith can cause obstructive jaundice and acute pancreatitis.

Definitive ALS therapy involves surgical bypass procedures, which are considered to be optimal. Surgical correction of any anatomical pathology that could lead to enterolith-mediated afferent loop stone formation must be performed to avoid recurrence.3 Although surgery has been the treatment of choice, such treatment cannot be indicated in 75% of ALS patients, who tend to be in poor general health, and to have peritoneal adhesions and carcinomatosis.9,10 In such patients, direct percutaneous decompression of the afferent loop via ultrasonography or endoscopy may be possible nonsurgical options. Endoscopic management of ALS has been considered to be technically difficult and few successful endoscopic approaches for the resolution of ALS have been reported.4,11 We used an endoscopic approach to confirm ALS diagnosis and to extract the enterolith. We identified an enterolith in the afferent loop and successfully fragmented the stone using EHL. The basic principle of EHL is the creation of a high-voltage spark between two isolated electrodes. These sparks are delivered in short pulses creating an immediate expansion of the surrounding liquid, inducing a spherical shock wave. This in turn generates pressure sufficient to fragment the stone. The EHL technique is generally used for endoscopic fragmentation of difficult bile and pancreatic duct stones. In addition, EHL has been successfully used in patients with duodenal obstructions secondary to biliary stone development, and in patients with gallstone ileus.12 Recently, an endoscopic approach featuring EHL has been shown to be effective in managing ALS caused by enteroliths.4 The procedural risk is low and the recovery period short. However, tissue damage and perforation risks are present, associated with both EHL specifically and endoscopy in general, if the anatomy is abnormal or altered. Thus, experienced endoscopists should perform the procedure. In addition, endoscopy using a transparent cap is recommended to overcome the sharp angulation and the long afferent loop associated with Billroth II gastrectomy.13

In conclusion, we successfully removed an impacted enterolith causing acute ALS by using EHL under direct transparent cap-fitted endoscopy. This method may be a valuable nonsurgical option for enterolith-induced ALS. However, for the prevention of recurrence of ALS, surgical bypass should be considered.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.

Notes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.