The Clinical Usefulness of Simultaneous Placement of Double Endoscopic Nasobiliary Biliary Drainage

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims:

To evaluate the technical feasibility and clinical efficacy of double endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) as a new method of draining multiple bile duct obstructions.

Methods:

A total of 38 patients who underwent double ENBD between January 2004 and February 2010 at the Asan Medical Center were retrospectively analyzed. We evaluated indications, laboratory results, and the clinical course.

Results:

Of the 38 patients who underwent double ENBD, 20 (52.6%) had Klatskin tumors, 12 (31.6%) had hepatocellular carcinoma, 3 (7.9%) had strictures at the anastomotic site following liver transplantation, and 3 (7.9%) had acute cholecystitis combined with cholangitis. Double ENBD was performed to relieve multiple biliary obstruction in 21 patients (55.1%), drain contrast agent filled during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in 4 (10.5%), obtain cholangiography in 4 (10.5%), drain hemobilia in 3 (7.9%), relieve Mirizzi syndrome with cholangitis in 3 (7.9%), and relieve jaundice in 3 (7.9%).

Conclusions:

Double ENBD may be useful in patients with multiple biliary obstructions.

INTRODUCTION

Surgical biliary drainage is usually accomplished through percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) or endoscopic biliary drainage. PTBD can be associated with adverse effects, including cholangitis, catheter dislodgement, hemobilia, bile peritonitis, liver abscess, and the possibility of malignant seeding [1,2].

Although endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) has disadvantages and possible adverse effects, including discomfort from the nasal tube, external drainage, migration, and a temporary nature [3], it is a less invasive procedure and has a low possibility of contributing to cancer cell spread [4]. Moreover, ENBD allows for the ability to gently irrigate turbid, purulent bile or blood clots, and can be used for cholangiography.

Single ENBD or endoscopic biliary stenting (EBS) may not be sufficient to drain multiple bile duct obstructions complicated with cholangitis or jaundice. In these cases, double ENBD using two drainage tubes may be useful. However, there has been no literature reported about the placement of two ENBD tubes. We therefore evaluated the feasibility, efficacy, and usefulness of simultaneous placement of double ENBD in patients with multisegmental cholangitis or multiple biliary obstruction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 38 patients underwent double ENBD between January 2004 and February 2010 at the Asan Medical Center (Table 1). This procedure was performed to drain multisegmental cholangitis or multiple bile duct obstructions. All patients were administered parenteral antibiotics before and after the procedure and hospitalized while the double ENBD tube remained in place.

We retrospectively evaluated demographic features, laboratory data, results of imaging studies, the indications for double ENBD, and the clinical course. Approval for use of the patients’ data was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan Medical College.

Double ENBD was performed using two radiofocus Jagwire guidewires (Boston Scientific Co., Marlborough, MA, USA), an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) catheter or papillotome (MTW Co., Düsseldorf, Germany), and two 5 Fr-nasobiliary drainage catheters (Cook Co., Bloomington, IN, USA). The ERCP procedures were performed using a backward oblique-viewing duodenoscope (TJF-260V, JF-260V; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) and fluoroscopy with patients under conscious sedation with midazolam and meperidine. Following selection of the obstructed bile ducts, two guidewires were sequentially inserted into separate bile ducts. Then, two ENBD catheters were inserted along the guidewires and simultaneously placed by withdrawing the duodenoscope under fluoroscopic guidance (Fig. 1). Patients with Mirizzi syndrome with cholangitis were drained by performing endoscopic naso-gallbladder drainage (ENGBD) and ENBD at the same time (Fig. 2). The tips of both ENBD catheters were pulled out through the same nostril at the same time using a Nelaton catheter (Fig. 3).

Double endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) in a patient with hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Bismuth classifi cation II). Unintended contrast fi lling and high-grade biliary obstruction with separated intrahepatic ducts (IHDs) were noted and contrast drainage was not accomplished during ERCP (A, E). After two guidewires were inserted in the two IHDs (B, C, F and G), the scope was extracted under fluoroscopic guidance, with a double ENBD tube deployed in both IHDs (D, H).

Images from a patient with Mirizzi syndrome treated with simultaneous endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) and endoscopic naso-gallbladder drainage with a double ENBD catheter. The endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography catheter was inserted further through a bile duct for deep cannulation into the cystic duct (A), following by insertion of a guidewire and its direction toward the cystic duct (B). Pus discharge thorough the opening of bile duct was noted during cannulation (E, F). A second guidewire was inserted into the right intrahepatic duct (IHD) and the ENBD catheters were passed along the guidewires (C, G). Finally, the scope was withdrawn with double ENBD catheters placed in the cystic duct and right IHD (D, H).

We defined multisegmental cholangitis as multiple bile duct strictures or obstructions complicated with cholangitis suspected due to fever, leukocytosis, abnormal liver function test, or purulent turbid bile. The average levels of white blood cell (WBC), serum bilirubin, aspartate transaminase (AST), and alanine transaminase (ALT) before and after drainage were compared by matched data analysis using a paired t-test. The laboratory data of post-double ENBD was obtained on the last day of double ENBD drainage.

RESULTS

Of the 38 patients who underwent double ENBD, 20 (52.6%) had Klatskin tumors, 12 (31.6%) had hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), three (7.9%) had strictures at the anastomotic site following liver transplantation, and three (7.9%) had Mirizzi syndrome (Table 1). Double ENBD was performed to relieve multisegmental cholangitis in 21 patients (55.1%), to drain contrast agent introduced during ERCP in four (10.5%), perform cholangiography in four (10.5%), drain hemobilia in three (7.9%), relieve Mirizzi syndrome with cholangitis in three (7.9%), and relieve jaundice in three (7.9%) (Table 2).

For all patients, mean duration of drainage with double ENBD was 14.1±15.2 days. The average levels of serum total bilirubin decreased from 10.9±0.9 to 8.7±11.6, and those of WBC count, serum AST, and ALT increased. The changes in laboratory parameters were not statistically significant (Table 3).

Twelve patients with HCC underwent double ENBD for 15.2±13.2 days. The average Child-Pugh score was 9.4±1.5. They showed an increase of serum bilirubin and AST level and a decrease of WBC count and serum ALT. However, there was no statistically significant difference. Contraindications for PTBD were found in nine patients with HCC: prothrombin time prolongation over 18 seconds in 7, moderate to severe ascites in 7, and multiple or disseminated mass in 8.

Twenty patients with cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) underwent double ENBD. During 10.5±10.8 days of double ENBD, WBC count, serum total bilirubin, AST, and ALT decreased. Of these, significant changes were noted in the levels of total bilirubin and ALT (Table 4).

All of the six patients with resectable tumors underwent surgery after an average of 14.8 days (range, 4 to 30) of double ENBD. Of these six patients, double ENBD was performed to drain contrast agent filling during ERCP in four patients, relieve cholangitis caused by previous EBS in one, and relieve jaundice in one (Table 5).

Three patients with stricture of anastomosis after living donor liver transplantation were kept on double ENBD for 46.3±18.8 days. These patients showed a decrease of serum bilirubin and an increase of serum AST and ALT (Table 4). All three patients with Mirizzi syndrome with acute suppurative cholangitis underwent cholecystectomy after improvement with double ENBD.

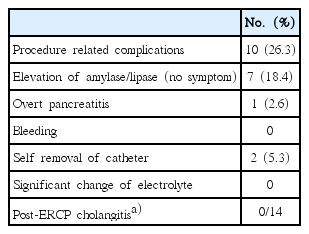

There was no procedure-related mortality. Pancreatic enzymes were elevated in eight patients after the procedure. Of these, endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) was performed in three and the other five were previously in the EST state. Overt pancreatitis was identified in one patient who improved after supportive care (Table 6). Post-ERCP cholangitis did not occur in 19 patients who underwent double ENBD for indications other than cholangitis.

Conversion from single to double ENBD did not cause additional discomfort such as swallowing difficulties or respiratory or nasal discomfort due to the double ENBD catheter. There was no significant change in concentration of electrolytes over the course of 4 weeks in the eight patients who were kept on double ENBD for a prolonged period (>4 weeks).

DISCUSSION

Double ENBD was effective, especially in patients with hilar CCA, Mirizzi syndrome, and biliary stricture, but less so in patients with HCC. The poor response in HCC may be due to uncompensated liver cirrhosis and the characteristics of HCC with bile duct invasion [5,6].

It was not easy to differentiate the cause of abnormal liver function tests in patients with HCC accompanied by liver cirrhosis and bile duct invasion. We could decide to insert a biliary stent or not and which duct should be drained by monitoring the output of double ENBD and the clinical course.

There has been no report about double ENBD, its efficacy, or safety compared with two stents in cases of hilar obstruction without cholangitis. Previous studies suggested that single ENBD in the future remnant lobe may be sufficient for preoperative drainage of B-C type I-III hilar CCA; and that both ENBD and EBS have the same effect of drainage [3,7,8]. However, multiple ENBD or PTBD may be helpful for B-C type VI hilar CCA [4].

It has been reported that extended resection for hilar CCA provides better long-term outcomes than limited resection [9,10]. Nowadays, ERCP has become an essential procedure as a diagnostic and drainage modality for hilar CCA. However, preoperative drainage with ERCP can provoke cholangitis, which may increase in-hospital mortality after combined hepatic and bile duct resection for hilar CCA [10-12]. EBS has a higher rate of cholangitis due to tube occlusion and regurgitation of intestinal flora than ENBD [13,14]. PTBD is more invasive than ENBD and has a risk of cancer seeding. Therefore, ENBD may be more favorable than EBS or PTBD for preoperative drainage in hilar CCA.

Double ENBD may prevent post-ERCP cholangitis caused by infused contrast media. Care should be taken that not too much contrast agent is infused into the separated bile duct in case of hilar CCA [7]. However, unintended contrast agent filling can happen. In that case, it is necessary to drain the intrahepatic segment to avoid cholangitis and double ENBD may be useful for this purpose. We also suggest that double ENBD may be helpful for hilar CCA or other conditions combined with multisegmental cholangitis, especially in cases of preoperative drainage. In our study, all six patients with resectable hilar CCA underwent surgery successfully.

Multiple drainage with biliary metal stents was accomplished safely and correctly in the proper bile ducts by performing cholangiography with a small amount of contrast media via double ENBD before stent insertion. Sometimes it may be difficult to select the proper bile duct for drainage and hazardous due to retained contrast media unless appropriate drainage is performed.

PTBD should be performed when hilar CCA is complicated with segmental cholangitis [15]. We experienced five cases of hilar CCA with multisegmental cholangitis that were improved successfully by double ENBD without PTBD. In cases of hilar CCA combined with cholangitis, double ENBD has some advantages as a temporary bridging therapy, including feasibility of monitoring drainage, maintaining patency with careful irrigation, and enabling cholangiography in addition to offering effective drainage.

It is rare that cholangitis occurs spontaneously in patients with HCC or hilar CCA. In the present study, previous EBS showed a significant correlation with multisegmental cholangitis. In cases of multisegmental cholangitis due to EBS occlusion, double ENBD has some advantages compared with biliary stents because early EBS re-occlusion is possible due to turbid bile, and separate bile ducts can be drained. Furthermore, when patients develop fever or showed aggravation of liver function tests, differential diagnosis can be easy during ENBD because bile color or output can be checked. This type of differential diagnosis is difficult after EBS placement.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has emerged as an effective palliative treatment for unresectable CCA, followed by the insertion of plastic or metal stents to ensure biliary drainage [16]. Double ENBD after PDT was useful in deciding whether to insert stents and in choosing plastic or metal stents simply by means of a cholangiography. It was also useful in draining obstructed bile ducts. Double ENBD before PDT was also helpful in treating multisegmental cholangitis and in deciding the location or length of bile duct lesion to be treated by PDT.

Simultaneous ENGBD and ENBD may be helpful to manage Mirizzi syndrome in selected cases. During laparoscopic cholecystectomy, ENGBD makes the cystic duct and its orientation more discernible [17]. After cholecystectomy, the remaining ENBD tube in the bile duct can be used for cholangiography. Even though unconscious self-extraction of the tube was observed in two patients, all patients were tolerant to double ENBD catheter without significant discomfort.

This study had limitations, mostly due to its small sample size and retrospective design. A relatively small number of patients were enrolled in this study because double ENBD was performed only in selected cases for which this procedure was expected to be beneficial. However, there has never been a report about double ENBD in the English literature, and our results suggest feasibility and usefulness of double ENBD under several conditions. Our study was designed to reveal the usefulness of double ENBD as a temporary drainage method in some situations that we experienced, but not to demonstrate the superiority of double ENBD compared with PTBD or EBS. Multicenter cooperative and randomized case-control studies are required to compare ENBD with other methods. However, it should be noted that drainage methods must be tailored to the situation of each patient.

In conclusion, endoscopic bilateral or multiple drainage with double ENBD using simultaneous placement of two drainage catheters was feasible, effective, and useful as a temporary bridging therapy for multisegmental cholangitis or multiple biliary obstruction.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.