INTRODUCTION

Currently, incidental findings of gastrointestinal (GI) subepithelial tumors (SETs) are increasing because of the implementation of national cancer screening endoscopy and the development of high-resolution endoscopy in Korea. The prevalence of gastric SETs reportedly ranges from 0.36% to 1.7% [1,2]. A decision is required at the time of discovery on whether the tumor should be further evaluated or if it can be observed with periodic follow-up. Indefinite decisions for SETs can result in poor cost-effectiveness with unnecessary endoscopy and emotional distress in patients, leading to poor compliance. Although endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), computed tomography (CT), and bite-on-bite biopsy may help in accurate diagnosis, these methods cannot always be performed for all SETs.

EUS is used to further characterize lesions through the examination of their layered structure, internal echogenicity, size, and relationship to the extramural structure. These provide additional information on whether the lesion is benign or malignant. However, although there are lesions with typical EUS findings, such as lipomas, duplication cysts, and heterotopic pancreas [3], hypoechoic lesions originating from the fourth layer, such as leiomyomas, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), and schwannomas, are difficult to distinguish with EUS alone. A previous study reported that the sensitivity and specificity of EUS in predicting malignancy was 64% and 80%, respectively [4]. Furthermore, the interpretation of the EUS image is dependent on the operator. Therefore, tissue acquisition through EUS-guided fine needle aspiration and biopsy (EUS-FNA/B) is needed for further differential diagnosis. EUS-FNA/B has the advantage of having the capability of visualizing the subepithelial layer, as well as reaching adjacent organs located in a difficult area to be aspirated by the previous endoscopic tissue acquisition modalities. In addition to its minimal invasiveness, EUS-FNA/B is preferred over CT-guided biopsy because it does not induce radiation and enables real-time visualization of the needle tip. However, it has limitations in aspect of difficulty in visualizing the needle tip clearly and consistently and interference of the image by bowel gas. We reviewed the indications for EUS-FNA/B in gastric SETs and the methods that can be used to increase the diagnostic yield.

INDICATION

The basic principle of EUS-FNA/B is to obtain information that can affect the patientsŌĆÖ treatment. EUS-FNA/B should be performed when the choice of treatment can be changed depending on the tissue diagnosis. If surgery is planned, the findings of EUS-FNA/B can change the selected surgical procedure. Clinically important SETs, such as leiomyomas, GISTs, schwannomas, heterotopic pancreas, SET-like carcinomas, and metastatic tumors can have a hypoechoic echo pattern and similar endoscopic features. For the accurate diagnosis of these tumors, it is important to obtain a sufficient amount of tissue so that the structure of the lesion can be sufficiently assessed and to enable immunohistochemical examination. Recent guidelines have recommended deciding the timing of tissue sampling based on the size of the tumor and high-risk features for malignancy on endoscopy and EUS (Table 1).

Tumor size

Current guidelines have suggested 2 cm as the cutoff diameter of SETs for further evaluation or periodic surveillance, despite the previously recommended cutoff of 3 cm by the American Gastroenterological Association [5-7]. The European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) recommended EUS for SETs less than 2 cm in the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum followed by periodic surveillance [8,9]. According to previous reports on the natural clinical course of small SETs, less than 2ŌĆō3 cm in size, during 24ŌĆō48 months of follow-up, there was no tumor-related death or a newly developed symptom related to disease progression, with only less than 8.5% of interval change in the tumor size [10,11]. Another study reported that GISTs less than 2 cm do not metastasize if the number of mitoses is less than 5/50 high-power fields (HPFs). In addition, despite the high rate of metastases of GISTs with a mitotic count exceeding 5/50 HPFs in the GI tract, small gastric GISTs showed exceptional results without increased metastases rates [12]. As asymptomatic SETs less than 2 cm harbor a very low risk of progression and usually show a benign clinical course, these tumors can be followed up periodically at intervals of 6 monthsŌĆō2 years [13,14]. However, SETs showing growth in size during the follow-up period should be further evaluated with tissue sampling for pathologic diagnosis, regardless of the size.

High-risk features on endoscopy and EUS

Gastric SETs, particularly mesenchymal tumors, such as GISTs, leiomyomas, or schwannomas, show similar findings on endoscopy and EUS. Therefore, efforts have been made to determine specific risk features that distinguish these tumors. Gastric SETs with high-risk features on endoscopy and EUS may have a clinically malignant potential. Biopsy or resection of these tumors is required to determine the long-term prognosis.

Large size (Ōēź2 cm), ulceration, irregular surface, and growth during the follow-up are significant features indicating potentially malignant GISTs [7,15-17]. As gastric neuroendocrine tumors and gastric carcinomas resembling submucosal tumors (by virtue of occurring in the submucosa) often present with a mucosal ulceration or an irregular margin, SETs with an ulceration or a depressed surface are recommended for biopsy to obtain a definite diagnosis [7]. Current guidelines suggest further evaluation, including CT scan, EUS, or EUS-FNA/B for SETs with malignant features on endoscopy [5-7].

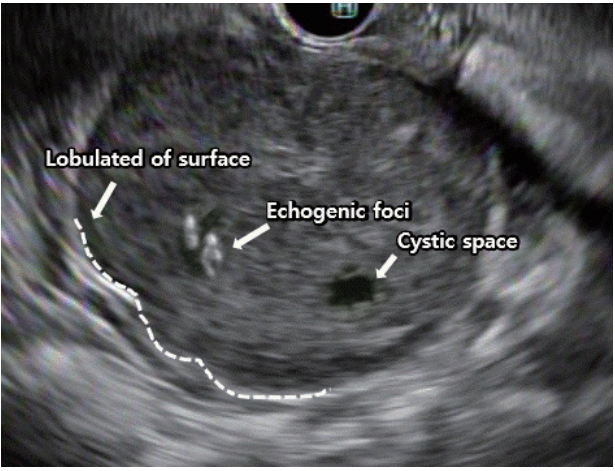

The Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society has identified high-risk lesions on EUS as those having an irregular border, internal heterogeneity, such as anechoic areas and echogenic foci, heterogeneous enhancement, and regional lymph node enlargement [15,18]. The well-known EUS findings that generally cause suspicion of malignancy include (1) a tumor size greater than 4 cm, (2) echogenic foci greater than 3 mm, (3) cystic spaces greater than 4 mm, (4) an irregular border, and (5) adjacent lymph node with malignant pattern (Fig. 1) [18-23]. The presence of at least two of the criteria from (1) to (4) predicts a malignant GIST with 80%ŌĆō100% sensitivity [19], whereas the combined presence of two of the criteria from (3) to (5) has a positive predictive value of 100% for a malignant or borderline gastrointestinal stromal cell tumor [18]. The optimal size for predicting malignant GISTs was reported to be 35 mm, with a sensitivity and specificity of 92.3% and 78.8%, respectively [24]. The combinations of these several features enable narrowing down the possible diagnosis and allow identifying malignant lesions.

DIAGNOSTIC YIELD

Although EUS-FNA/B has the strength of having high sensitivity and high specificity, its sampling adequacy and diagnostic rates were reported to be only 74.5%ŌĆō83.0% and 71.0%ŌĆō83.9%, respectively [25-28]. The diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA/B is influenced by many factors, including the nature of the target lesion, degree of technical difficulty of the procedure, size of the needle, number of needle passes, use of suction, use of a stylet in the needle assembly, special maneuvers to procure better-quality tissue, such as the fanning technique, availability of an on-site cytopathologist, and experience of the endosonographer (Table 2).

Nature of the target lesion and patient

Transesophageal and transgastric EUS-FNA/B with a straight scope position result in a higher diagnostic yield than does transduodenal EUS-FNA/B with an angulated scopetip position [29]. The diagnostic yield is also influenced by the patientŌĆÖs age and the location of the tumor. A patient age of under 60 years and a lower third location of an SET are predictive factors of an inadequate tissue yield in EUS-FNA/B [27]. When the tumor size was divided into 2-cm intervals of 0ŌĆō2, 2ŌĆō4, and Ōēź4 cm, the diagnostic rates were 71%, 86%, and 100%, respectively [28].

FNA needle

Needle choice is based on the consideration of the following: the ability to acquire adequate cellular material for accurate diagnosis, flexibility to approach the tumor, and minimal complications. Currently, needles for EUS-FNA are available in 4 sizes, including 19, 20, 22, and 25 gauge (Table 3). A 19-gauge needle with its larger bore is considered to acquire larger tissue samples and to provide better cellularity than that of fine needles [30]. However, because of the possibility of blood dilution of the specimen and reduced maneuverability in areas with sharp angulation, a large-bore needle does not necessarily lead to favorable outcomes with a higher diagnostic yield [31,32]. Therefore, for tumors located in the fundus or antrum, a 22-gauge needle is often preferred because of its maneuverability in angulated areas. In addition, lesion types such as GISTs and lymphomas may need a large-bore needle because their diagnosis requires specimens with preserved tissue architecture [33,34]. Meanwhile, a recent meta-analysis and systemic review showed no significant difference in the accuracy and complication rates between the 22-gauge needle and the 25-gauge needle, with the 25-gauge needle only showing a small advantage in acquiring an adequate sample [35,36]. Recently, a new generation of flexible 19-gauge core biopsy needles has been introduced, which has shown promising results for lesions requiring a transduodenal approach [37]. A Korean EUS study group compared a 22-gauge aspiration needle with a 22-gauge biopsy needle for sampling SETs, and reported that the EUS-FNB group had significantly higher yields of histological core samples and higher diagnostic sufficiency rates [38]. In addition, EUS-FNB with a 20-gauge ProCore needle is a technically feasible and effective modality for histopathologic diagnosis of gastrointestinal SETs, providing adequate core samples with fewer needle passes [39].

Number of needle passes

The number of needle passes required to achieve the highest diagnostic yield vary widely. The presence of an on-site cytopathologist is the main factor influencing the number of needle passes, in addition to the characteristics of the lesion (cystic or solid) and its location [40]. In multivariate analyses, although the number of needle passes was not found to be a significant factor for the adequacy of collected specimens [25,26], gastric SETs have shown an 83% sample adequacy with 2.5 needle passes, a diagnostic accuracy of 83.9% with 5.3 needle passes, and the plateau of diagnostic accuracy was reached with 2.5ŌĆō4 needle passes [25,26,41].

Use of suction

The role of suction during EUS-FNA is still controversial. However, depending on the nature of the target lesion, the effect of suction utilization may be different. In vascular-rich lesions, such as lymph nodes, suction may result in blood dilution, thus yielding poor-quality samples. A randomized controlled study reported that the use of suction resulted in better cellularity, more blood in specimens, and no improvement in diagnostic yield [42]. On the contrary, in fibrotic lesions or solid masses, suction may enable acquiring adequate samples [43-45]. In several studies, cellularity, accuracy, and sensitivity were higher in the suction group than in the non-suction group [46,47]. However, in another randomized controlled study, suction did not improve the diagnostic yield of FNA [47]. A previous study on the suction method recommended the use of suction in lesions suspected to be mesenchymal tumors, considering the reported cohesiveness of mesenchymal tissue [48].

Stylet

The use of a stylet has been proposed to optimize the diagnostic yield of tissue acquisition in solid lesions. This method prevents the needle tip from being contaminated or blocked by a plug of gastric wall tissue before reaching the target lesion, thereby increasing the ability of tissue aspiration and improving the quality of the specimen. However, randomized trials have demonstrated that the use of a stylet during EUSFNA does not improve the diagnostic yield and cellularity [49-51]. The use of a stylet is not recommended considering the labor used to reinsert the stylet and the prolongation of the procedure time. In addition, insertion and retrieval of the stylet may be difficult in angulated areas because of the bending of the endoscope. Furthermore, re-use of the stylet during the second and third tissue acquisitions increases the risk of needle stick injury. However, most investigators use a stylet during puncture for removing the aspirated sample from the slide.

Fanning

Fanning is a technique for acquiring specimens from multiple areas through a single puncture, in which the needle is moved back and forth in a fan shape by using the elevator and the up/down dial control of the endoscope. The fanning method has been used to improve the diagnostic yield, particularly in cancerous tumors with a necrotic center. In a study on pancreatic masses, fanning resulted in fewer numbers of passes needed to obtain a diagnosis, with a high first-pass diagnostic rate [52]. Although SET is often not a cancerous lesion having a necrotic portion and may be firm when located in the muscular layer, the fanning technique is still expected to increase the diagnostic rate by collecting tissue from multiple sites of the tumor.

On-site cytopathologist

The presence of an on-site cytopathologist is considered to be a key factor for the diagnostic sensitivity in EUS-FNA [53], as it improves the diagnostic yield, increases the adequacy of samples, and reduces the number of needle passes [54-59]. Previous studies have reported that the presence of an on-site cytopathologist increased the rates of sample adequacy by 10%ŌĆō29%, resulting in a 10%ŌĆō15% increase in the diagnostic rate [45,60,61]. However, many hospitals do not have an available on-site cytopathologist. In a recent study conducted to overcome these limitations, gross evaluation of the adequacy of samples, such as macroscopic on-site quality evaluation (MOSE) or rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE), by an EUS examiner resulted in improvements in the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA [62-65]. By using MOSE, when the presence of a macroscopic visible core of more than 4 mm was considered to indicate an appropriate specimen, the macroscopic evaluation failed in only 7% of cytology samples and in 13.5% of histology samples [63]. According to the ROSE study, endosonographers who underwent extensive training in processing techniques with a pathologist tended to need fewer needle passes than those who performed FNA without ROSE. According to these reports, gross evaluation of the adequacy of samples by endosonographers may be sufficient in deciding the number of needle passes when no cytopathologists are available.

CONCLUSIONS

EUS-FNA/B is a minimally invasive and effective diagnostic method that plays an important role in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal SETs, which, in turn, have a decisive impact on making appropriate treatment choices. Although the tumor size that requires EUS-FNA/B has not been established, current guidelines have suggested that tumors >2 cm and having malignant features, such as ulceration and an irregular border, require a pathologic diagnosis through EUS-FNA/B. Recently, new-generation flexible needles with improved diagnostic yield have been introduced. According to the characteristics of the SETs, a suitable FNA/B needle should be used and various methods such as the use of a stylet, the suction method, and the fanning technique should be appropriately employed to improve the diagnostic yield of EUS-FNA.